The letter to the Hebrews is essential for our understanding of the concept of priesthood in the New Testament, as it focusses on the priesthood of Christ himself and the accompanying changes under the new covenant. The first three chapters provide a necessary introduction, explaining that Jesus, although fully human, is higher than the prophets, including Moses, higher than the angels, also, and in fact the one through whom everything was created, who is “the pioneer of salvation” of “many sons and daughters” and to whom everything is subjected. A key verse to remember is 2:11 – “Both the one who makes people holy and those who are made holy are one of the same family. So Jesus is not ashamed to call them brothers or sisters”. Note that within the priesthood of Aaron, the brothers of a priest would have been priests themselves.

Before the author discusses Christ as our High Priest, we have another introduction in chapter 4, dealing with Sabbath-rest for the people of God. Although many, even before the time of David, “had the good news proclaimed to them” (verse 6), they “did not go in because of their disobedience”. The heart of the matter, as explained in Psalm 95:10,11, which is partly quoted in Hebrews, was that “they are a people whose hearts go astray, and they have not known my ways”. This was clearly not only related to a lack of Sabbath keeping, although the Sabbath is often used as shorthand for the law of Moses. As a result of their hearts going astray (not of one particular transgression) many were not permitted to enter the rest which was provided by the Promised Land.

Christ is our “rest”

What Hebrews is saying next, is that even the Promised Land was not the ultimate fulfilment of this idea of “rest”. What God is after, is that we rest from our works of self-justification and self-congratulation, and start to rely on grace. There is a sense in which God also expects self-reflection, just as He ceased from his work of creation to consider what He had made. In any case, God does not want us to just continue on the automatic pilot, not even when we think we are following his commandments. So probably the most significant function of the Sabbath as well as Israel’s arrival in the Promised Land was to remind people of the vastly more important spiritual rest of being reconciled with God by “resting from their works”.

Many groups are still getting this wrong, whether they are Sabbatarians, those who think the Church is mainly about Sunday worship, those who vehemently support the expansionism of the state of Israel, or those who still believe that their “works” contribute to their salvation. All these groups have in common that they are focussing on a kind of literal rest or a feeling of having arrived. Paradoxically, their literal and sometimes fanatical obedience often results in a spiritual disobedience. However, as verse 13 makes clear, “nothing in all creation is hidden from God’s sight”.

Christ our High Priest, our access to the Most Holy

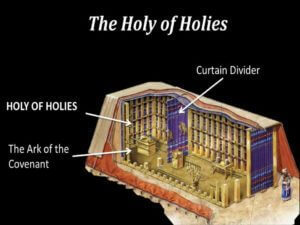

It is at this point that the author introduces Christ in his capacity as our great high priest. He is not only great because of what has been said in the previous chapters about his divinity, but also because he is able to “empathise with our weaknesses”. Verse 16 draws the conclusion that we should therefore “approach God’s throne of grace with confidence”, both to “receive mercy” and to “find grace to help us in our time of need.” In the earthly tabernacle the throne of grace, also called the mercy seat, was to be found in the Holy of Holies. It rested on the Ark of the Covenant and together it was the only piece of furniture in this Most Holy department of the temple.

It is at this point that the author introduces Christ in his capacity as our great high priest. He is not only great because of what has been said in the previous chapters about his divinity, but also because he is able to “empathise with our weaknesses”. Verse 16 draws the conclusion that we should therefore “approach God’s throne of grace with confidence”, both to “receive mercy” and to “find grace to help us in our time of need.” In the earthly tabernacle the throne of grace, also called the mercy seat, was to be found in the Holy of Holies. It rested on the Ark of the Covenant and together it was the only piece of furniture in this Most Holy department of the temple.

Many Christians and even theologians don’t fully realise how revolutionary the call in verse 16 actually is. All believers are invited to approach the throne of grace, and to do so even confidently, thus entering a space formerly reserved for the High Priest! This seems to confirm that we are actually brothers and sisters of Christ and that (through him) we belong to the same priestly order. Of course such membership is only possible within a new order of priesthood, which will be introduced in chapter 5. However, it is more than a promise. It is current reality. We are invited to approach the throne of grace now. Access was granted when Jesus died on the cross, crying out with a loud voice. At that moment the veil between the two departments of the earthly temple was torn from top to bottom (Matthew 27:50-51a), which is very unusual, you might say, supernatural. The trembling of the earth and the splitting of rocks further indicated that a new age with a totally different priesthood had commenced.

How reality differs from shadows and symbols

Just to be absolutely clear, we are not speaking of believers entering an earthly temple. The temple of which the veil was torn, was left “desolate” (destroyed by the Romans) in 70 A.D., just as Jesus prophesied in Luke 13:35. From the time of the crucifixion all that mattered was the temple in heaven. Having said this, the temple in heaven is not an exact replica of the earthly temple in the way that the earthly temple represented the heavenly one. If it is true what chapter 10:19-20 says, namely that the real “curtain” is actually Jesus’ body, with Jesus opening for us “a new and living way” into the Most Holy Place, then the Holy part of the temple represents the earthly period before the ascension, and the Most Holy represents the heavenly period after Christ’s earthly life.

It would then make sense if only a Most Holy Place (not a Holy one) would be found in heaven, for this was the realm to which Jesus ascended. However, even the Most Holy is only “up there” in a spiritual sense. Revelation 21:22 describes a New Jerusalem, coming from heaven, which has no temple in the city, “because the Lord God Almighty and the Lamb are its temple”. The same applies to heaven in the period between the ascension and the second coming of Christ. There is no literal section in heaven where some priestly ministry is carried out. All ministry was completed by Christ on earth.

When Christ returned home, to sit on the right hand of the Father, and to sit on his very throne, that represents a realm which was his and will be our final destination. Rev. 5:6 speaks of “the Lamb standing in the centre of the throne”. And of “the one who wins the victory” Christ says in Rev. 3:21, “I will grant him to sit with Me on My throne just as I also have won the victory and have taken My seat with My Father on His throne.” In other words, there are no separate thrones for the Father, the Son and the believers. Neither is there a distinction between the throne of power and the throne of grace.

The mercy seat being the main piece of furniture in the Most Holy, I don’t think we would make a terrible mistake by treating the throne, the Most Holy and heaven as synonyms. This is further supported by Isaiah 66, where God says that heaven is his throne. However, if the Lord Almighty and the Lamb are themselves a temple (Rev. 21:22), this is a further reduction of complexity. All that matters is now God, the Three in One. After all, when we receive grace, it is not from a throne, but from God. The throne is just a symbol which clarifies that God has the authority to rule and to forgive. We don’t need to go to heaven to appear before the throne of grace as priestly brothers and sisters of Christ.

Errors separating us from Christ

Based on what we have seen so far, Christ does not literally have to plead for us in heaven, as if the Father himself would not be capable of being merciful and as if the Father and the Son do not share the same throne. It is especially strange to think, as Adventists do, that Christ only entered the Most Holy in 1844. How could the author of Hebrews, already in his days, invite every believer to appear before the throne of grace, if Jesus himself had (according to them) not even entered the “place” where this throne resides?

However, mainstream churches do not need to look down on such weird ideas when they themselves often teach or imply that we cannot appear before the throne of grace without using a variety of “means of grace” or sacraments which are controlled by a specially selected professional priesthood. Unfortunately all these teachings have had the effect (if not theologically then psychologically) of keeping us at some distance from the abundant grace of God and away from taking the priesthood of all believers seriously.

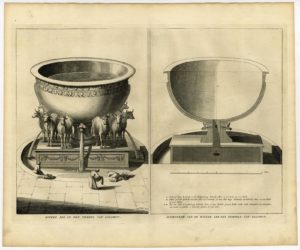

Other sanctuary items are “missing” from heaven as well, in other words: no longer necessary, like the “sea” (thalassa) of Revelations. 21:1. Many expositors refer to the absence of the sea as symbolising the absence of danger. The sea has also been linked with judgement (think of demons being driven into the water in Luke 8:30-33). However, the sea is also the name for the vessel used by the Old Testament priests for ritual cleansing.

In this context, the “sea” simply represents a requirement for priests to be able to perform their work and enter the temple, which requirement is no longer applicable, because we are already clean in Christ. This is one of the first things reported in the book of Hebrews: “When He had made purification of sins, He sat down at the right hand of the Majesty on high” (1:3). Finally, the “sea” has been linked to baptism. In that case the sea is absent from heaven because the ones called to appear before the throne of grace are assumed to have been baptised. The great Reformer Luther confirmed that baptism is the only requirement for becoming a priest under the new covenant.

Our first conclusion must be that there are considerable differences between the earthly temple and the “heavenly” one. Since in heaven things are perfect, the only thing that can really symbolise it, is heaven itself. The earthly temple represented both this perfect state of affairs (by having a Most Holy Place in it) and our separation from it. To suggest that baptised Christians are not priests, having free access to the Most Holy and the throne of grace, is a serious matter, because it throws us back into the old, imperfect situation of being separated from God by a thick curtain, representing a Saviour who has not yet died for us.

An entirely different order

Neither the priesthood of Christ, nor the priesthood of all believers, would have fitted in the Old Testament scheme. Like the earthly temple reflected both the perfect and the imperfect, harmony and separation, so the old Aaronic priesthood came with its own limitations. Many aspects of the work of the priest pointed to Christ, but some might give you completely wrong ideas, like the repeated sacrifices. That is why chapter 5 introduces the order of Melchizedek.

On pictures like these, Christ is shown as high priest of the “wrong” priestly order. The letter to the Hebrews makes it clear that Christ is not a successor of Aaron, but head of the order of Melchizedek.

Although the person of Melchizedek is still only used as a symbol of Christ, some of his characteristics are more fitting than the “symbol” of Aaron. For instance, Melchizedek was both a priest and a king, like Christ would be. We don’t know where he came from, like Christ was born of a virgin. He lived before Aaron, so this order is more ancient and fundamental, like Christ existed before Moses. The name Melchizedek is old Canaanite for “My King is Righteousness”. Christ is considered to be the “Sun of Righteousness” predicted in Malachi 4:2. Compare John 8:12 where Jesus calls himself the light of the world. Melchizedek shared bread and wine with Abraham, which can be thought of as a reference to the Eucharist, the body and blood of Christ.

Perhaps of equal importance are the things which are not mentioned. The order of Melchizedek is not said to be hereditary. God can say to anyone, “You are a priest forever, in the order of Melchizedek” (Hebrews 5:6, Psalm 110:4), as indeed He said to Jesus. Before drawing any further conclusions, the author of Hebrews warns us in verses 11-14 that the whole subject is hard to explain. This is not because it is not logical, but because at some point, his Jewish readers (the Hebrews) had resisted the whole idea and gave up trying to understand. And I believe there is still a temptation to regard Christ as just an improved version of a Jewish high priest. Even in many Christian pictures He is shown in the garments of a Jewish high priest.

Resistance to something so revolutionary

Both Jews and Christians seem to have considerable difficulties with the discontinuity involved in such a radical change of priesthood. Perhaps the most dangerous thing is that Christ can call others to follow him into this priesthood, which no longer requires sacrifices, and that He in fact calls everyone to follow him through that veil of his death and resurrection, which is symbolised by our baptism. However, our hesitations and reservations about this new order are no excuse. The author of Hebrews rebukes his readers in verse 12, saying, “though by this time you ought to be teachers, you need someone to teach you the elementary truths of God’s word all over again!”

In chapter 6 we read about some of these elementary things and of the author’s wish to move beyond them. He describes Christians as “those who have tasted the goodness of the word of God and the powers of the coming age”. He also compares them to “land that drinks in the rain often falling on it”. In that case a useful crop is also expected. If that does not happen, the land is called “worthless” and even “in danger of being cursed” (verse 8).

Often in scripture, “bearing fruit” refers to good behaviour, but that does not seem to be the case here. After all, verse 10 speaks of “your work and the love you have shown him [God] as you have helped his people and continue to help them”. Those fruits apparently already existed. The problem seems to be an inability to “inherit what has been promised” (verse 12), which would be possible through faith and patience. In this chapter the words “inheritance” and “heir” occur several times. It is as if verses 1-12 are saying that if we don’t move forward, we will move backward, which will be like “subjecting the Son of God to public disgrace” (verse 6).

The nature of the promise

So what promise are we talking about? This is not a trivial question, because “God wanted to make the unchanging nature of his purpose very clear to the heirs of what was promised” by confirming it with an oath (verse 17). In chapter 7 this oath is defined as the same “You are a priest forever in the order of Melchizedek” from Psalm 110:4 which we already came across in chapter 5.

This leaves the question how ordinary believers can inherit a promise which has been confirmed by an oath made to Christ. The answer is given in 6:19,20. Our hope is compared to an “anchor for the soul, firm and secure. It enters the inner sanctuary behind the curtain, where our forerunner, Jesus, has entered on our behalf”. He has done what we could not have done, hence “on our behalf”. However, once Christ went through, it became possible for us to enter as well. We are not yet in heaven (at least not in the sense of the afterlife), but we have this anchor, assuring that we will be. Furthermore, we can already claim this inheritance through faith.

Just as the Bible teaches us that eternal life does not start sometime in the future, but already when we accept the life which is in Christ, so we can also regard heaven and the throne of God (the Most Holy) as realms which can be entered already. This is often regarded as a mystical experience. I am sure that is included. However, the text explicitly calls Jesus our forerunner. This means that the way to God lies open as we speak. Even if we lack the faith to enter or don’t have enough patience with ourselves to get used to the idea, we are priests already.

Like the priests of old, we are ordained before we actually enter the temple. What is new is that we are ordained by our baptism. Revelation 1:6 says that Christ has made the faithful “a kingdom, priests to his God and Father.” These words are part of the introduction of the Book of Revelation, so that it does not belong to any visions about the future. Christ has made us priests, full stop. Can we accept this, or do we have difficulty moving “beyond the elementary teachings about Christ”? If so, when will we be ready to teach our fellow-disciples about their priestly calling?

Sons and daughters of God

When we look more closely at Hebrews 5:5, we notice that Psalm 2:7 is also being used to support the fact that “Christ did not take on himself the glory of becoming a high priest”. This means that the author considers sonship of God as connected to the honour of becoming a priest, an honour which “no one takes on himself” (verse 4). When Jesus was baptised, there was a voice from heaven, declaring “This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased” (Matthew 3:17).

Many are so familiar with Jesus being the Son of God, that they underestimate the implications. If someone is the son of God himself, he is at least worthy of being a priest who stands before God. This is what “Son though he was” in 5:6 points to. In other words, being a son in itself already qualified Jesus to be a priest. However, on top of that, “he learned obedience from what he suffered and, once made perfect, he became the source of eternal salvation for all who obey him” (verses 8 and 9) and that is when he was designated by God to also be high priest (verse 10).

So what is the implication for us? At the beginning of this article I asked you to remember Hebrews 2:11 – “Both the one who makes people holy and those who are made holy are one of the same family. So Jesus is not ashamed to call them brothers or sisters”. When Jesus is not ashamed to call us brothers and sisters, it means that on the basis of Hebrews 5:5, we, too, are designated by God to be priests. It is not an honour we take on ourselves.

So what is the implication for us? At the beginning of this article I asked you to remember Hebrews 2:11 – “Both the one who makes people holy and those who are made holy are one of the same family. So Jesus is not ashamed to call them brothers or sisters”. When Jesus is not ashamed to call us brothers and sisters, it means that on the basis of Hebrews 5:5, we, too, are designated by God to be priests. It is not an honour we take on ourselves.

There are two important remarks that need to be made at this point. First, although we are asked to follow Christ into the Most Holy, this does not mean we are high priests. This is an important difference with the priesthood of Aaron. An ordinary priest would never be allowed into the Most Holy. However, those who have been taught by Jesus to call God “our Father” are allowed to come before the Father’s throne of mercy. Secondly, Christ became the source of salvation for all who obey him (verse 9). If we disregard Christ’s commandments, He cannot lift us up, because we don’t allow him to do so. In Matthew 12:50 Jesus says, “Whoever does the will of my Father in heaven is my brother and sister and mother”.

Of course, priests in the order of Melchizedek should obey Christ. However, we do not read about any additional requirements. It cannot be shown from the Bible that disciples must obey Christ while priests must obey him more. Neither is it true that the standards for disciples are lower than those for priests, for the simple reason that these two groups are identical! How would we measure holiness, anyway? Fortunately Christ said, “Take my yoke upon you and learn from me, for I am gentle and humble on heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For my yoke is easy and my burden is light” (Matthew 11:28-30 NIV). This is still true in the context of priesthood, as Hebrews 4:15 plainly tells us that “we do not have a high priest who is unable to empathize with our weaknesses, but we have one who has been tempted in every way, just as we are—yet he did not sin.”

This is also why Hebrews 10:19 says we can “have confidence to enter the Most Holy Place by the blood of Jesus“. Confidence to enter the Most Holy place does not mean to stay on the outside and appoint certain representatives to go in. Neither does it mean, like Adventists believe, that only Christ has entered, in order to carry out some “Investigative Judgement”. It means that as many as believe in Christ are invited follow Him in “a new and living way, opened for us through the curtain, that is, his body” (verse 20). It is no presumption when we act like priests under Christ. It is simply what we are called to be and to do. It was quite a discovery for me to find that becoming a priest is not for a select group. It is something we can all embrace with confidence.

An eternal and final order

An explanation why the order of Melchizedek is greater than the one of Aaron and has made the latter obsolete, can be found in Hebrews chapter 7 and following. I will not go into the details here. You can read it for yourself. Here I just want to draw your attention to two consequences that tend to be overlooked. First, since Jesus was without sin, his sacrifice was sufficient to overcome death and therefore it was the last sacrifice ever needed, at least for that purpose (7:27). This means that the renewed order of Melchizedek is eternal. No other priestly order needed to follow it, for salvation to be possible for all.

Secondly, the order did not end with Christ’s death on the cross. At that time He became High Priest. In that sense the renewed order only just properly started. An order implies multiple priests, and so does having a High Priest. We have just seen that no more sacrifices were needed. Apparently we can have priests without sacrificial duties, except of course, for the requirement to “present our bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to God” (Romans 12:1).

However, that requirement applies to all Christians. It is explained in the next verse as our readiness to be transformed and further discern and follow the will of God. So here is another confirmation that all can and should be priests. Because there are no Christians who are not required to perform this very practical “ritual” in their lives. This priesthood is neither linked to bringing animal sacrifices, nor to presumptions of taking the place of Christ, but simply to what we are in Christ and to the resulting attempts to live a holy life, dedicated to God.

If it ain’t broken, don’t try to fix it

In the previous section we have seen that the Bible mentions two orders of priesthood, namely the one of Aaron and the one of Melchizedek. In Biblical times God initiated no other orders. Today, if a small segment of Christians is called priests (or behaves as an elite), this cannot be the priesthood of Aaron, since that order is part of Judaism and also requires animal sacrifices, thus denying the true Lamb of God, who gave himself once and for all to take away the sins of the world. Neither can it be the order of Melchizedek, since that (eternal) order applies to all baptised Christians.

Besides, this “third” priesthood has extra requirements, even when it comes to holiness and representing Christ to the rest of us. This ancient but unbiblical distinction is maintained in spite of much evidence that priests or clergymen in such orders are not necessarily holier than “ordinary” Christians. The distinction is even maintained in spite of sins which have done irreparable damage to the reputation of the whole church, causing many to lose interest. Unfortunately, similar distinctions exist in churches which avoid the word “priest”, so using different names and titles is no solution.

The complaint which summarises all others is that a fair number of clergy, especially among the higher clergy, are secretly or openly looking down on those who do not belong to their inner circle. One thing that always gives it away is one-sided communication. There is even a name for this: clericalism. Historically, the term “clericalism” was used to indicate the strong influence of the clergy on public matters, education and politics. Nowadays it also refers to alternative ways in which churches are hanging on to power or ways of justifying an inward focus. The more the Church shrinks and becomes dependent on die-hard members, the more a kind of love-hate relationship may develop between sub-groups. Members unfairly tend to blame the clergy for not making the church grow, while the clergy unfairly tends to blame the laity for not taking more initiatives (without necessarily being fully empowered to do so). Neither group realises that this whole issue would not exist if we did not have two groups trying to shift work and responsibilities to each other.

Although the vast majority of the clergy are dear and hard-working people, there is a growing number of justifications for asking whether we actually need such a “third” order. Don’t get me wrong. I am not asking whether we need those people or whether we need their ministry. There is no question about that. I am asking whether we really need this emphatic and pervasive distinction between clergy and laity. Without the “third” order, the people in question would still be priests, namely in the general order of Melchizedek. They would still have their ministries, as well. However, the most serious source of clericalism would have been eliminated, namely the false belief that clergy are a separate and “higher” category of Christians with somehow a special hotline to heaven. I also wonder if it is even possible to belong to two priestly orders at once, when one of them emphasizes equality and the other requires a degree of inequality. The other day there was some discussion in the Netherlands as to whether wordly judges should be allowed to suspend clergy after they committed abuse. Some priest quickly responded that their office cannot be taken away, only the exercise of the office. This is just one of many confirmations that even after causing tragedy, their first concern is often not for the victims, but for a potential loss of status. Many really believe that once “ordained” they are a special species and owners of irrevocable divine protection.

Clericalism is not just a rare and easily avoidable extreme. Even when identified and actively opposed, an attitude of superiority continually and almost inevitably pops up as a consequence of the clergy-laity dichotomy itself. The reason is the unnecessary dualistic view of Christianity. Those clergy that do not suffer from clericalism, suffer from the arrogance of peers and superiors. Clericalism has caused us to look at the clergy as providers and the laity as recipients. To quote the famous former pastor, now successful life coach and communication expert, Paul Scanlon, “Every Sunday all church-goers are liberated, but usually they do not reach freedom“. It is much like the people of Israel who kept their slave-mentality long after they had been liberated from Egypt. Many were either complaining consumers or submissive followers of whatever leader happened to be in charge. Some imitated their Egyptian slave-masters. The only answer is radical equality and individual responsibility, values I believe Christ proclaimed. Clericalism and passive Christianity will not disappear by top-down “encouragements” of “discipleship” in the laity, but only by no longer distinguishing two classes.

Excuses

The counter-argument is usually that the clergy are really shepherds and teachers, and not everyone can be a shepherd or a teacher. Didn’t St. James write in his letter (3:1) that “not many of you should become teachers, my fellow believers, because you know that we who teach will be judged more strictly”? Does that not mean that they are held to higher standards? Yes and no. We are all judged according to the light we have received and the light we claim to have.

The Greek word for judgement (krima) can also be translated (and in the New Testament often has been) by “condemnation”. It is logical that an influential person who demonstrates distinctly un-Christian behaviour or teaches nonsense, cannot hide this forever and will receive more condemnation from the betrayed community than one who has limited influence. Nowadays more and more people see through those clergy who lecture people about love and holiness, while secretly abusing minors and other vulnerable people or protecting abusers. They no longer want clergy who are rubbing shoulders with the rich and powerful at the expense of the average or poor individual. They have had enough of those vain actors, flattering those they need, while they should be advocates of justice, truth and compassion who invest in the personal growth of each and everyone in the community.

My claim here is that the extra responsibility is connected with public ministries, not with our fundamental priesthood. However, if one claims what in fact amounts to a “double” priesthood, yes, then the extra responsibility is connected to the public ministry which is sometimes erroneously called contemporary “priesthood”.

What Christian teachers should cover

Furthermore, the text in St. James must be balanced with the remarks of the author of Hebrews. In chapter 5:12 he addresses an entire community of people, all of whom, he says, “by this time ought to be teachers”, but who have given up trying to understand anything beyond the basics. Here the qualification for becoming a teacher is: having “trained oneself to distinguish good from evil” (verse 14) and understanding “the teaching about righteousness” (verse 13), which obviously includes understanding the order of Melchizedek as discussed in this letter to the Hebrews. In other words, a teacher is one who is trained in distinguishing good from evil, who understands that he is a priest in the order of Melchizedek thanks to the righteousness of Christ, and who teaches others that they, too, as equal brothers and sisters of Christ, are included in the same priesthood.

If we go by this definition, based on the book of Hebrews, more people are (or should be) teachers than are currently recognised as priests or clergy. This is (for different reasons) even admitted by the church, at least by those denominations where teaching is not limited to the clergy. Lay ministers play an important, though still underestimated, part in this type of work. Something similar can be said of the role of shepherds (pastoral work). So if teaching and pastoral work are given as reasons for having a separate (third) order of priests, those reasons are simply inadequate. Instead, the Church should work towards an honest recognition and revival of the existing and utterly inclusive priesthood of Melchizedek.

Of course there could be other, more organisational reasons, for having a category of people with a managerial (leadership or supervisory) role, but if this coincides with an order of priests which, by its very existence and by its prerogatives (if not its failures) obscures and discourages the wider order of Melchizedek, this cannot have been Christ’s intention. Also, the more managerial roles are often the very ones with which the local clergy is struggling. Sometimes they are given (or assume) too much authority and sometimes too little. Surely, one cannot claim a leading position without risking to offend a few people who refuse to grow spiritually. Could the emphasis on status have arisen (very early in history) as a substitute for true enabling leadership, which should be the only thing distinguishing presbyters / elders? Did we as “ordinary” priests, from that time onward have to be called “the congregation” or “the people”? Why do we still have special courses in “discipleship” for the laity, as if the clergy have nothing to learn with regard to following Christ?

In other words, it is excellent to have various ministries, even a “threefold” ministry of bishops, presbyters and deacons. However, this does not make such leaders more priestly than they already are within the order of Melchizedek. On the contrary, such ideas or suggestions could actually make them less saintly. Neither is it right to act as if we can have two distinct “orders” under one High Priest, with two separate initiations. This is just as undesirable as having several “Christian” denominations which do not recognise each other as true brothers and sisters.

Strangely enough there are various initiatives towards closer cooperation as denominations, but there are hardly any initiatives to break down the barriers between clerical orders and the order of Melchizedek. If the Church wishes to convince people that they matter to God and that they will not just be “members” of some community, paying the salaries of the professional clergy; if the Church really wants to share the responsibility for reaching the lost, they will do something about the unjustified clericalism by addressing it on a theological as well at a practical level. Attempts to solve the issue with lip-service to equality and calls for more cooperation between clergy and laity will fail as long as a faulty ecclesiology remains in place.

Conclusion

The Biblical teaching on the order of Melchizedek, a.k.a. the priesthood of all believers, which was rediscovered by Martin Luther, only to be almost forgotten again, clearly deserves more attention. I believe that failure to do so will result in further secularisation and perceived irrelevance of the Church. Hierarchy is the last thing that speaks to people. There is enough of it outside the Church. What a breath of fresh air it would be if all Christians would recognise one Lord and (membership of) one single priestly order with Christ as its High Priest. We would be many steps closer to being “real” brothers and sisters, standing before God as his sons and daughters, and therefore as priests, through faith and the merits of Christ.

This post is also available in: Dutch

YOU ARE INDEED A BLESSING TO THE BODY OF CHRIST. I PRAY THAT EVERY READER BE ILLUMINATED AND RECEIVED THIS TRUTH. MORE GRACE!.

The following quote from St. Augustine is also relevant for how we understand heaven and our appearance before the throne of mercy: “Just as [Jesus] remained with us even after his ascension, so we too are already in heaven with him… Christ is now exalted above the heavens, but he still suffers on earth all the pain that we, the members of his body, have to bear… While in heaven he is also with us, and we while on earth are with him.”

– Augustine, Sermon for the Lord’s Ascension (430 AD)