This is the second of two essays about the history and future of Reader ministry in the Church of England. If you have not read my first essay, I strongly recommend doing that first. The problems outlined there are no doubt causes why clergy, as well as Readers themselves, continue to struggle with the identity and role of Readers. In 2009 the “Upbeat” report and its recommendations had been accepted by the General Synod as something to be discussed in the various Dioceses. Unfortunately, this simply did not transpire in any noticeable way. Other problems were apparently considered more pressing. As Reader morale had prompted this report in the first place, to see it almost completely being ignored was not exactly uplifting.

Part of the problem had been the creation and rise of various other, partially overlapping, lay ministries. In some parishes just about anyone was allowed to preach, although this was officially condemned by the bishops. At the same time, opportunities for Readers to lead complete services had diminished. Finally, because of earlier privileges[1] and theoretical responsibilities given to Readers, it had become somewhat difficult to distinguish them from priests, especially with people becoming less knowledgeable about church offices and rules. This had prompted representatives of the clergy to increasingly emphasise the distinction between the clergy and the laity.

I will never forget two separate scholarly chaplains confessing to me that in their opinion, all ordained ministers should have a “normal” job and serve the Church without compensation. Vice versa, this would definitely also increase the chances of those who hold down such a job, to be ordained. The Church has, literally as well as figuratively speaking, paid a price for abandoning the biblical pattern. It was then only logical that stipendiary ministers would always, to a certain extent, even if only subconsciously, feel uneasy in relationship to those offering their services free of charge.

This is not a cheap shot at the clergy. They could not reasonably be expected to undermine their own source of income. We call this type of mechanism a “perverse incentive” and it exists whether you think you can control it or not. It is bound to reduce to a greater or lesser extent the chances of voluntary workers being allowed into clergy “circles” unless the situation is fairly desperate. Even then, Church laws and attitudes will tend to resist an optimal symbiosis. If Readers were to be given more room to define their own ministry, these tensions would only increase, I am afraid, so I don’t think a fourth revival of Reader ministry is very likely.

This is not a cheap shot at the clergy. They could not reasonably be expected to undermine their own source of income. We call this type of mechanism a “perverse incentive” and it exists whether you think you can control it or not. It is bound to reduce to a greater or lesser extent the chances of voluntary workers being allowed into clergy “circles” unless the situation is fairly desperate. Even then, Church laws and attitudes will tend to resist an optimal symbiosis. If Readers were to be given more room to define their own ministry, these tensions would only increase, I am afraid, so I don’t think a fourth revival of Reader ministry is very likely.

Preparing the big Anniversary

There was, however, a festive occasion coming up, namely the commemoration of 150 years Reader ministry in 2016. So what could be done towards an Upbeat 2.0? If you have run out of solutions and compromises there is just one more thing you can do, which is to present the problem as if it is the solution. It is one of the techniques in the advertising world, similar to “if you can’t beat them, join them”. For instance, in Holland a chocolate bar with too much air in it, so that it was cheap to make and profitable to sell, was marketed as a very “light” snack. I am not saying this technique is always used deliberately. Sometimes it happens spontaneously, because other more profound options have been rejected.

So what to do when you believe in your heart that ministry belongs to the clergy and you have already made a few complicated exceptions, but you still want to activate the “untapped” cheap resources that are out there? In the Readers Conference of April 2014 Bishop Robert Paterson (responsible for Reader ministry) called for more diversification of lay and ordained ministries. Some dioceses had indicated to “not want Readers in their traditional form”. Others had questioned the role and the value of the CRC (Central Readers Council), the only body which gives Readers a voice![2]

One of the first observations in the report from the conference was that “with decreasing numbers of clergy, the role of the laity is becoming more important”. This should sound familiar to you by now. However, it did not say that the role of Readers was becoming more important. One could be forgiven for getting the impression that the Church was once more going for a pragmatic and temporary solution. To counter that impression, it was added that “there is a theological case to be made for developing more lay ministries”. At this point, the article referred to a paper by Susanne Luther, which appears to have been removed from the CRC website since. I would have liked to see the theological case for developing a variety of lay ministries as opposed to just a variety of ministries.

Secondly, Reader training was found to be not standardised across the dioceses. Should we have more standardisation then? No, “in some parishes, what is needed is not a theologian trained to diploma level, but a well-informed Christian who can lead worship well”. Sounds familiar, too, right? Over-qualification. Now even Readers were no longer considered enough in touch with the common people. “There is evidence of gifts that are very different from the traditional academic scholar’s way of working”. No kidding!

Then, after describing the original vision for Readers as “reconnecting church and society”, the bishop stated that “Readers have become more clericalized – they look more like vicars”. Do I hear any regrets there? That must be it, for if you have allowed and even required Readers to become almost as overqualified and out of touch with society as yourself and they even look like clergy (not without your permission), you might have to ordain them, which cannot possibly be true. There is no mention of any questions during the conference about Readers being called “clericalized”.

Did no one wonder how it could be that “clerical” had a negative connotation when applied to Readers, while the “clerical” behaviour of the clergy continued to be celebrated as simply part of their vocation? In other words, it is all right when you pass certain additional tests. For a good example of double standards, look no further. It would be different if Readers were doing things that were not allowed or deviating from what they had been taught, but that was not the case, at least not for the vast majority. So this generalisation was distinctly unfair.

The Church then tried to find a way to discourage clerical behaviour in Readers, while not leaving them totally discouraged. Potential critics and those who were a bit confused should of course be turned into allies. What makes Readers ‘special’ was “in the eyes of the leadership of the CRC, the combination of theologian and lay… to interpret the world to the church and the church to the world”. In this context, the term “theologian” comes across as a misplaced compliment. Let me explain.

On the one hand it is an overdone compliment because the term “theologian” is normally only used for people with a Master’s degree in theology. Readers usually do not even have a Bachelor in Theology, although they may have other academic qualifications. Personally, I would not dream of calling myself a theologian, even though (or because) I have a Bachelor in Theology. The proposed “definition” was not entirely new. It had been coined by a former Bishop of Newcastle, Alec Graham, then Chairman of the ACCM (Advisory Council for the Church’s Ministry) in 1984. He said that Readers should become ‘the Church’s lay theologians, thinking, well-informed, articulate…. theological resource people’.[3] I happen to know that at the time, academic standards for clergy and pastoral workers were lower than they are today. In our contemporary context the “definition” is misplaced also because the very diploma Readers receive had just been called “not always needed” and was seen as part of the reason why, supposedly, Readers increasingly failed to connect Church (i.e. clergy) and society.

On the one hand it is an overdone compliment because the term “theologian” is normally only used for people with a Master’s degree in theology. Readers usually do not even have a Bachelor in Theology, although they may have other academic qualifications. Personally, I would not dream of calling myself a theologian, even though (or because) I have a Bachelor in Theology. The proposed “definition” was not entirely new. It had been coined by a former Bishop of Newcastle, Alec Graham, then Chairman of the ACCM (Advisory Council for the Church’s Ministry) in 1984. He said that Readers should become ‘the Church’s lay theologians, thinking, well-informed, articulate…. theological resource people’.[3] I happen to know that at the time, academic standards for clergy and pastoral workers were lower than they are today. In our contemporary context the “definition” is misplaced also because the very diploma Readers receive had just been called “not always needed” and was seen as part of the reason why, supposedly, Readers increasingly failed to connect Church (i.e. clergy) and society.

The other part, about interpreting the Church to the world and vice versa, also raises questions. The expression dates from 1884.[4] Please forgive me if I deliberately exaggerate the issues a little, for the sake of clarity. Would it not be sad if the clergy would really still depend on interpreters for their grasp of what goes on in the world? Would it not be sad if their jargon and organisation were still such that, without extra translations, their message would be incomprehensible to the secular world? Is it not the task of a priest to be that additional interface between God and the people?

Is it not the task of everyone, including the clergy, to “reach out beyond the traditional confines of the Church”? Is the “vision of 1866” not once more a projection into the past of a modern (delegated) activism and “market” orientation, born out of a shrinking number of church members? Of course it was never the intention that the clergy would do everything by themselves. However, on a tight budget, even supporting that outreach now proved to be too much. Rather than simply admit they needed help with providing the necessary support, representatives of the clergy were resorting to ever more convoluted descriptions of lay ministry in order not to have to regard lay ministers as genuine colleagues. These descriptions are bound to change again, as all descriptions do, but what if they are already inconsistent or outdated at the time of their introduction? If there had been an even lower budget, this collegiality would already have happened out of sheer necessity.

Finally, the question was asked during the conference if Readers should be linked more closely to the Ministry Council which currently looks after ordained ministry only. The Ministry Council, as represented by its director, Julian Hubbard, promised to look at resources, licensing and encouragement for lay ministries in general, but not specifically for Readers. The contours of where the Church was heading with Reader ministry slowly became visible. Other, more “frontier” type, lay ministries would be encouraged. It remained unclear how these other ministries would be able to connect the church and society if that was sincerely supposed to be the expertise of Readers. What would the “enabling” look like? Would Readers first have to interpret the Church’s message to the other lay ministers, after which these other lay ministers would interpret and deliver that to the world? A rather unlikely scenario, just to show the inconsistencies involved here.

Discipleship and Ministry

In the Summer of 2015 Bishop Robert showed a particular interest in getting some of the terminology right, albeit for the pragmatic reason that “our failure to do so is seriously delaying decisions and actions”.[5] He then made a sharp distinction between disciples and ministers. I could follow him in that, but he also, quite unnecessarily, opposed the idea of every member having a ministry of some kind. He wrote that the concept of “every-member-ministry” was “biblically unsustainable”[6]. Only ministers could minister. Elsewhere, in the Summer 2016 edition of The Reader, he wrote “To be a Reader is to emphasise the fact that your primary ministry is … being a disciple… bringing him [God] into the conversation”. Here the distinction between a disciple and a minister was suddenly absent!

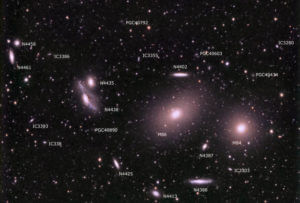

Going back to the earlier article, Readers were then compared to a small section of a whole “galaxy of lay public ministers”. Just think about this analogy! There is this galaxy of public ministers, of which Readers are only a part. The rest of the laity must live in separate galaxies since they have no public ministry. The clergy also live in a separate galaxy, since they have public ministries, but are not lay. Now wait a minute… They might not even be part of the same universe, since all the other galaxies we have mentioned are lay galaxies, in the strict sense of not being clergy. Would the clergy really be living in another universe?

Can we now please get back with both feet on the ground and admit that we are a hopelessly divided bunch of churches, fractured internally as well, and inhabiting a tiny planet, who need to get rid of a number of delusions of grandeur in the interest of our very survival? If we were really to have as many ministries as there are stars in the sky, would that not bring us closer to the dreaded “every-member-ministry”? Would the cost not rise proportionally with the number of ministries that would need to be facilitated? Or would the Church then say that the laity needs to support itself? Some Readers were still looking for things to do, right? Fair enough, but how would the trainers be trained? Currently there is not even a clear picture of the ministries that would have to be facilitated. Most importantly, could such a giant change still be implemented top-down?

In the same issue of The Reader, CRC Secretary Alan Wakely explained that the future of Reader ministry was increasingly being determined not in the CRC but in the Ministry Council, technically [as well as in reality!] a subcommittee of the Archbishop’s Council. This Council was only created in 1999, which was after I joined the Church.

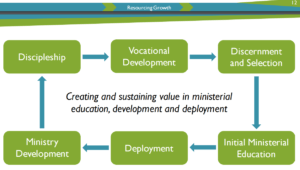

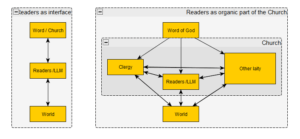

The relationship between discipleship and ministry. I like this official diagram as it does not speak about clergy and laity. The reality is much more complicated and expensive as the clergy laity distinction does play a significant role and an increase in types of ministry is proposed as well.

The Archbishop had “pressed to go for growth both in basic discipleship and also in ministry, without which the increase in disciples will not happen.” Actually, there was mainly a drive to increase the number of ordinands (candidates for the priesthood) by 50%. There were “various recommendations to enable many more people to be ordained, and both to lower the average age and also to make it easier for candidates over 50”.[7] Although there was some money available for “dealing with issues of lay ministry”, whatever they were, no comparable drive to increase the number of lay ministers was mentioned. Not based on any of the facts he himself had just given, Alan still concluded that “at long last, the important role that laity will play in the future seems finally [sic] to have been recognised in the church’s corridors of power”.

The opposite was the case. Research by the RME (Resourcing Ministerial Education) around every diocese had found “a desire for more clergy. ‘A priest in every parish’ is said to be a foundation stone for growth.”[8] Bishop Robert tried to suggest, probably in vain, that this should rather be “a minister in every community”. He then came up with the following names for Readers: lay-parsons, local ministers, community-parsons (as supposedly intended in 1866) and pioneer-theologians. “Licensed Lay Ministers” (LLM) was not (!) a good name because that stood for several (the galaxy of) public lay ministries.

He then stated that standards for Readers and Reader selection must not slip. For he had seen evidence across the dioceses that selection had been less rigorous than should be expected. What was the point he tried to make? There are similar failures with clergy selection procedures. These procedures are nowadays very much based on the same selection criteria. Such generalisations, without presenting the actual lessons learnt, are of no use to individual Readers. They only show how easily the position of Readers can be undermined by a few complaints. No number of conflicting ideas about names and tasks was going to solve this.

The idealised past and the ambiguous present

In the Autumn 2015 issue of The Reader, Bishop Robert described the role of Readers in the early days after 1866 as “re-connecting the Church with the people” (after a period of increasing urbanisation) and as “pioneering work on the boundaries between church and world”. He immediately contradicted himself, saying that Readers only gradually “shifted from assisting the clergy to become more and more like lay-parsons.”

The earliest example he gives is from 1941 (75 years later!) when Readers were allowed to read the epistle, administer the chalice and preach. Therefore the heart of their ministry in the early days before 1941 could hardly have been, as he claims, to explain the Scriptures, let alone to be pioneers. In spite of this, and of the fact that “for at least three generations the Church has been looking among the same type of people with the same gifts as ordinands to select as Readers”, he calls it a “categorical mistake” for Readers to be considered or to consider themselves as even clergy-like. Was this not the same bishop who said that Readers had clericalized? How can we be clericalized and not be clergy-like? Since when does one not reap what one sows?

Celebration of 150 years of Reader ministry

On the 6th of May, 2016, it was time for the solemn service at All Souls Langham Place, to commemorate 150 years of Reader Ministry. I know many vicars who are opposed to making announcements in a sermon. Some are even opposed to making announcements before the blessing. Bishop Robert Paterson (Chairman CRC) actually managed to use his sermon for announcing the probable dissolution of the CRC, the body in which Readers are organised, to be replaced by “something like a lay ministry council”.[9] A proposal to that end had already been affirmed by the AGM.

If it was announced during the sermon, it must be very good news, right? The new council would also have to fund regional lay ministry projects, so that it would be able to show some results. As we noted before, the usefulness of the CRC had been questioned, so then you dismantle your only organisation and start projects with money that would otherwise be spent by other committees on equally useful projects. Then you end your sermon with, “The future is exciting for this movement. Confidence is returning. It’s Ascension Day.”

As announced by the Archbishops of Canterbury and York, the chair of the CRC has since been taken over by Bishop Martyn Snow. It is worth noting that he also became a member of the Ministry Council, with a particular brief for lay ministries. This was clearly not done by accident, as it would obviously make it easier to transform the CRC into a lay ministries council. When I asked my colleagues what they thought of this transformation, I got only one cryptic answer, namely “Readers will always be Readers!”

She was blissfully ignoring all the issues but was at least consistent with the bright future which was always held before Readers, no matter what happened inside or outside the Church. It did not prevent them from going extinct several times and having to be resurrected several times. My concern did not get any smaller when I discovered that the CRC, which is based in the UK, is actually an independent charity and not an official organisation within the Church of England. Therefore, even though it is chaired by a bishop, the Church of England can deny any responsibility for what goes on in the CRC, which includes any information spread via its magazine, The Reader.

A change in language

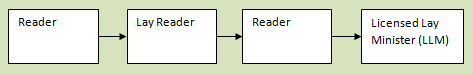

I don’t know how many times, lately, I have heard or read things like “confidently lay”, “proud to be overwhelmingly lay” (sounds a little like ‘proud to be gay’), “emphasis on lay-ness”, and “no clones of the clergy”. It is important to note that this language has varied over time. From times immemorial, the term has been Reader or lector. Then at some point, perhaps to create more distance to the Catholic minor order, it became Lay Reader. Some people still call me that. Then the Church realised that this is a silly name, because there is no such thing as an ordained Reader, either. Therefore to say “Lay Reader” is like a double emphasis on the fact that you are lay. So they changed it back to Reader. Apparently, the Church was not too comfortable with this, either. Bishop Robert Paterson calls it “a badly understood title”.[10]

So in 2009, they invented something rather clever. Why not call these people Licensed Lay Ministers (LLM)? Not very long ago this had been regarded as not specific enough. Also, some still found it hard to accept that lay people could be “in Ministry” at all. However,  it solved many problems. There was sufficient distance to the ancient Catholic office of Reader, the term “Lay” was reintroduced (but not expressed twice), and the authorisation was clear. By initially only using it for Readers (and for the time being leaving the name Reader as an alternative) Readers would still feel recognised. The title, however, could easily be used for other lay ministries as well. They wanted to strengthen these and bring them on board, anyway. Eventually, Readers would just be a blood type in a “galaxy” of lay ministries, all to be firmly controlled by licenses from the bishop. If they died out (again!), it would not be so conspicuous, because there would still be LLM’s before and after. An extra advantage of including the word “licensed” in the name of the office, could be that when the license is terminated, you would lose your title as well. By definition, it could not remain your title for life. Currently, Readers have a certificate of admission as well as a license. The former remains when the latter is terminated. This resembles the situation for priests.

it solved many problems. There was sufficient distance to the ancient Catholic office of Reader, the term “Lay” was reintroduced (but not expressed twice), and the authorisation was clear. By initially only using it for Readers (and for the time being leaving the name Reader as an alternative) Readers would still feel recognised. The title, however, could easily be used for other lay ministries as well. They wanted to strengthen these and bring them on board, anyway. Eventually, Readers would just be a blood type in a “galaxy” of lay ministries, all to be firmly controlled by licenses from the bishop. If they died out (again!), it would not be so conspicuous, because there would still be LLM’s before and after. An extra advantage of including the word “licensed” in the name of the office, could be that when the license is terminated, you would lose your title as well. By definition, it could not remain your title for life. Currently, Readers have a certificate of admission as well as a license. The former remains when the latter is terminated. This resembles the situation for priests.

“The thinking that lies behind the use of ‘licensed lay minister’… is for Readers to be one group in a galaxy of lay public ministers”.[11] It was not a matter of simply replacing one title by another. The bishop continued, “Forget the titles. Get the understanding right and the titles can follow!” Well, Bishop, I fully agree. Stop fiddling with the titles. Let’s get the understanding right. Of course, the clergy should then also forget about their titles and first get the understanding right. Does “shared ministry” really require a distinction between clergy and laity (in terminology)? I also agree when you write “Here’s the bad news: Readers must adapt and change”, but there is no need to lecture us about this. Readers and MSE’s are probably exposed to more change and change management than you can imagine, especially when we combine what we experience in the secular world and the Church.

What is not very helpful, though, if I may speak for all Readers, is constant change just to follow different moods and hypes, in the words of Ephesians 4:14, being “blown about by every wind of new teaching”. How do we know that future generations will not look back at our latest obedient adaptations and call them “drifting”[12] as well? Where is the solid theology behind all this? Which concrete changes are meant, anyway? Seeing ourselves as one group within a larger group of public ministers (lay and ordained) is not new, after all.

Safety and exclusivity at the center of the Church

The answer, as I understand it, was that Readers were meant to further shift their activities from traditional church settings to the world outside. To this end, Bishop Robert made fun of “holy buildings with coloured-glass windows and pointed arches”. Either he could not see the value of religious art and architecture, which I doubt, or by implication, he was claiming these very things for exclusive use by the clergy. This would be unfair as these spaces are not owned by individuals. I do not want to press this argument too hard, but if anyone has made these things possible financially, it has been the laity. With time, it has only become more difficult to reach people with words only. We cannot compare our time to the much more religious 19th Century.

In our visually oriented day and age, many are rediscovering the value of images and rituals. Even groups of young people have started to rediscover the authenticity and timeless value of ancient rites and symbols. In June 2017 Olivia Rudgard wrote about a new study which suggested that “levels of Christianity were much higher among young people than previously thought. […] Around 13% of teenagers said that they decided to become a Christian after a visit to a church or cathedral. […] The influence of a church building was more significant than attending a youth group, going to a wedding, or speaking to other Christians about their faith.”[13] Pen Wilcox writes, “Not until I was ordained as a Methodist minister and became a pastor to a congregation did it gradually dawn on me that for some worshippers the words are subsidiary… [They] love the wood panelling, the stained glass, the gothic arches…”[14] All these things tell us a story of their own, which is often more powerful than our painstaking efforts to respectfully inject religious considerations into largely secular discussions in the outside world.

I am not saying it is impossible or not right to get people’s attention with words, but I am reminded of St. Francis’ well-known saying, “Preach the gospel, and if necessary, use words”.[15] Preaching by means of your way of life, however, is something all Christians should be able to do. The way I see the task of clergy and Readers alike is to live this kind of life and to teach other Christians to do the same. The verbal part of this can easily be done in a church setting, or in small groups, which I consider to be extensions of the Church.

Mandy Stanton, a Reader and Lay Ministry Development Officer, writes, “We are reminded at our licensing that part of our role as Readers is ‘to encourage the ministries of God’s people, as the Spirit distributes gifts among us all… (and) to help the whole Church to participate in God’s mission to the world.”[16] Then she refers to Ephesians 4:12 about equipping the saints for the work of ministry! Surely this is more than just being a “bridge between the chancel and the nave”, as another description of Readers goes. [17]

Neil Hudson of the London Institute of Contemporary Christianity once remarked that Readers “as they minister to the people of God in our churches, can liberate people to engage in the full mission of God”.[18] Why is this so? As one Reader in full-time employment put it, “I want to be a Reader so there is someone at the front, leading worship and preaching, who understands the pressures of the people in the pews, someone who can include real life issues”.

Only then will we get a realistic approach to mission which involves the whole people of God. If that does not satisfy the hierarchy, it is just too bad. One cannot at the same time view Readers as the voice of the laity and the secular world and then ignore their insights and findings. In 2009 the Church seems to have registered only one thing, namely “under-use”. This one-dimensional observation opened the gates wide for all kinds of nostalgic plans and speculations, but it basically betrayed a lack of careful listening.

It is also important to look at the situation, churchmanship and gifts of a Reader. It makes a big difference whether a person is retired from his or her secular job or not. The type of mission depends very much on the type of the local chaplaincy. If, however, the task of all Readers is ultimately to be restricted to teaching non-Christians, i.e. pure evangelism, or to training evangelists, then why not just appoint pioneer evangelists and stop admitting new Readers? Of course, these evangelists should not be allowed to preach in church, for that would be too “clerical”. The Church could then honour its commitment to the remaining Readers by allowing them to preach “from the chancel steps” or on the streets until the age of 70. Currently, the average age of Readers, especially in the UK, is rather high, anyway. The unpleasantness would not last long.

More change in language

In May 2017, “European” Readers and Readers in training met in Cologne, Germany. I did not attend, so I can only go by the written summary,[19] but even from that, a few interesting observations can be made. Firstly, the title speaks of Lay Ministers, so that seems to have become the normal title already.

Secondly, LLM ministry is described as being “on the frontier of Church and world”. On the one hand, we are said to be “in the position of having a listening ear in two camps”. However, attendants of the conference committed themselves “to move to the frontier”. Judging by this second statement, they were, until then, not yet in the right position with their listening ears. Things were clarified when I read the advice of Stephan McNally of the LICC (London Institute for Contemporary Christianity) to first identify our “front-lines” for ministry. Apparently, these front-lines are not always so clear that we can instantly move there. This may also explain why the summary only speaks of listening and not yet of concrete actions.

Thirdly, and perhaps most importantly, terms like “Frontier”, “front-lines” and “camps” figure quite prominently. They bring with them connotations, not only of exploration (to boldly go where no man has gone before = pioneering) but also of war. In 2009 the “Church Army” was held before us as the great example, transforming whole communities. After we have witnessed a war on drugs and a war on terrorism, are we now to start a war on atheism and church-avoidance? The “Setting God’s people free” report (GS 2056) actually quotes a 1946 (end of WWII) report, saying, ”The Christian laity should be recognised as the priesthood of the Church in the working world, and as the Church militant in action in the mission fields of politics, industry and commerce.”[20] We all know the song “Onward Christian Soldiers” and St. Paul also uses a military term or two. When he says, “I have kept the faith” (2 Tim. 4:7) the original language “carries the meaning of having guarded the faith as an armed soldier would guard his post against enemy attack. Paul was saying that he had not strayed from the truth of God’s Word, that he lived it out.” Note that this was a defensive, not an offensive strategy. If we defend our faith from certain external influences and attacks, thus keeping it genuine, we will also be more successful in attracting others.

Finally, at one point the summary spoke of Readers listening to the world and the Church. I noticed that two sentences later, their ministry was said to be about listening to the world and the Word. Church and Word were used interchangeably. The underlying assumption was that listening to the Church is just about equal to listening to the Word of God. If that were so, we could save ourselves the trouble of listening to the Word of God! In reality, I think there is a unique interaction between our experiences in the world and our understanding of the Word of God. This will enable the Church to learn something they could not otherwise learn from just studying the Word and its own tradition. Besides, Readers are part of the Church they are meant to listen to. Also, the rest of the laity cannot be left out of the equation! I have summarised and compared the two approaches in the diagrams on the right.

Thy Kingdom Come

In May 2017 the Archbishop of Canterbury’s prayer initiative was running for the second time. Its aim: to increase the number of conversions by prayer. This time the participation was much greater with other denominations joining the initiative as well, so in that sense, it was a success. On the home page of its website (www.thykingdomcome.global ) the Archbishop is quoted as saying “I cannot remember in my life anything that I’ve been involved in where I have sensed so clearly the work of the Spirit”. Actually, he was not just involved in it. It was, as Christianity Today called it, his “brainchild”. Even if the work of the Spirit could be clearly felt, I think it would have been more effective to quote someone else, since it is always thought to be difficult to objectively judge one’s own initiatives. Then I thought, maybe we should grant the Archbishop this little indulgence in the light of his obvious enthusiasm, example and hard work.

Next, beginning of June 2017, I read an interview in Christianity Today about “Thy Kingdom Come”.[21] The Archbishop explained the wide support for the initiative as follows. “Giving permission to Christians to do things their own way has been crucial. The days when the Church of England could issue diktats instructing people how to do things have gone. Partly due to lack of resources from the centre, churches have been liberated to be creative.” When did this happen? As we have seen, a lack of resources has existed in many different periods. What exactly had changed? How is it that the Church could ever prescribe a way of doing things for the laity, since they are not employed by the Church, apart from specific lay ministers having made promises of obedience? In what way had entire local churches been liberated to be creative? Had they only been liberated to contribute to Church growth or also in other ways, for instance by allowing more inclusivity? The decision to think about special services for transgenders had not been made at this point! Did the Archbishop know what the Synod would later decide about this?

Note that, in the interview, the news about the abolishment of diktats was not a direct quote. The only relevant part of the interview which was recorded literally was when Welby spoke of the “enabling of a vision that touches people’s imagination without being too prescriptive about how to live it out”. Aha, so the Church does still prescribe ways of evangelising, but perhaps less than they used to. Which made me even more curious which things had actually changed and when.

The Renewal and Reform website has a separate page on “Setting God’s People Free”. There, “at the outset, to avoid misunderstanding” it is emphasised that the report in question “looks beyond and outside Church structures”. The liberation in question, therefore, takes place in a realm outside Church jurisdiction (apart from the obvious restriction on public ministers that they should at no time, by their conduct, give the Church a bad reputation). Liberation is therefore not the right word. If anything, it should be “encouragement to be creative”. After all, rules and diktats which don’t exist in a particular realm cannot be lifted. I guess the reason for still using the word “liberation” must therefore have been for public relations purposes.

The report “Setting God’s people free” itself explains that the “goal is not one of re-organisation. Rather it is about redemption”. Let me see. If this is about redemption, the word “liberation” could have been used in the theological sense of being liberated from sin, “chaos and absurdity”, and lack of confidence. It could be about being called “into the life of his Kingdom”. Unfortunately, that was also denied in the report. “What needs to be addressed is not a particular theological or ecclesiastical issue but the Church’s overall culture. This is a culture that overemphasises the distinction between sacred and secular”.

Well, I could not agree more with the last sentence, but surely a culture that overemphasises the distinction between sacred and secular must be based on a theology that overemphasises the distinction between sacred and secular. This distinction is very old, originated in primitive religion and has survived in the Church until now.[22] Even as people say they want to reduce the over-emphasis, they still cling to lots of different realms with different rules. For instance, when “lay leadership” is mentioned, everyone thinks about leadership in the Church. Wrong! The Church wants the laity to show leadership outside the Church. Leadership within the Church falls under the LMWG (Lay Ministries Working Group), leadership elsewhere falls under the LLTG (Lay Leadership Task Group).

Of course, if the new freedom would have had any consequences for Reader ministry, I would have known or should have been informed. If there had been any change in the clergy-laity dichotomy, I would certainly have known. In the meantime, my experience with Church regulations over the past 22 years was that, if anything, they were gradually being made more complex. Not only the “vision” but much of the “imagination” as well, was “enabled” top-down rather than bottom-up. People could contribute whatever they wanted, as long as this did not introduce important changes to the central structures. However, real changes of culture often do result in re-organisation. That is usually the whole point of culture changes.

The logo of “Thy Kingdom Come” contained what looked like cross-hairs and a kind of target, obviously pointing to targeted prayer. Although the Archbishop was eager to emphasise that “Thy Kingdom Come” was not only about evangelism, the target was clearly to have more people converting to Christianity and joining a church. Two well-known pitfalls are when the Church is too easily identified with the Kingdom of God and when the front door of the church gets more attention than the back door. The best basis for evangelism, I believe, is a spiritual community which is honest about its rules and power structure and supports all its ministers and workers. It does not help to suggest a measure of freedom that does not exist, at least not within the organisation.

Not tackling the main problem

The report “Setting God’s people free” contains several abbreviated stories that are supposed to “illustrate the shifts that are needed”. Here is one from page 5, along with my comments.

“Within four days I met three people with a great deal in common who were exploring Ordination. All were around the age of 50, all were playing key leadership roles in their local Churches, all had senior jobs and spoke of the confidence with which they lived out their faith in the workplace. I could not help feeling a sense of sorrow that three such competent lay leaders felt the need to explore Ordination so I pushed them quite hard. One woman told me that she felt that being Ordained [notice the capital ‘O’; ed.] was the only way to ‘get her voice heard in the Church.’ All three spoke about ‘wanting to do more for Jesus.’ I tried to explain to them that Ordination was not ‘doing more’ but ‘doing something completely different.’ It was not the next stage in a Christian journey but was about putting an end to a significant lay ministry in order to start afresh with something wholly different. I am not sure to what extent I got through. The episode made me realise how little we honour lay leadership despite years of trying. It has caused us to rethink the way our vocations team explore a candidate’s sense of call, and especially to probe that expression, ‘I want to do more.’”

Let me make it quite plain that I agree that “wanting to do more” is not a good reason to seek ordination. Neither is getting your voice to be heard in the Church. What I find quite serious, however, is how ordained ministry is apparently still depicted as wholly and completely different from lay ministry. This is in plain contradiction to the stated goal of the report, namely to remove the overemphasis on the distinction between the sacred and the secular. Furthermore, the idea that ordination cannot be “the next stage in a Christian journey” flatly contradicts the experience of most people who have ever been ordained. They all had a lay ministry of some sort before their ordination.

Let me make it quite plain that I agree that “wanting to do more” is not a good reason to seek ordination. Neither is getting your voice to be heard in the Church. What I find quite serious, however, is how ordained ministry is apparently still depicted as wholly and completely different from lay ministry. This is in plain contradiction to the stated goal of the report, namely to remove the overemphasis on the distinction between the sacred and the secular. Furthermore, the idea that ordination cannot be “the next stage in a Christian journey” flatly contradicts the experience of most people who have ever been ordained. They all had a lay ministry of some sort before their ordination.

It is totally unsatisfactory to just feel sorry for these 3 women, to feign regret about the Church’s inability to express more appreciation for lay ministry, and then to push future candidates even harder. The selector, or whatever his or her role was, wondered if he or she “got through”. Without knowing any of the people involved, I can assure you the answer would have been negative. It is simply impossible to convince someone that laity and clergy are “equal in worth and status… and equal partners in mission” by emphasising how completely and utterly different the clergy are to the laity or how different their tasks are! This still echoes medieval ideas about the ontological transformation of priests into another species. It is absolutely shocking to find this in the same report which claims to want to change Church culture with regard to this very issue of sacred and secular.

Even Readers, who are one moment considered as already too much “clericalised”, may suddenly be treated as complete strangers to the mysterious and well-guarded world of sacraments and “ecclesial” ministry. They, too, are to be cast into the modern straightjacket of self-employed pioneering. It may or may not be a coincidence that this trend resembles neoliberal political ideas in which it is “everyone for oneself”. Three things will be rewarded in this giant “market place”: success (conversions or providing employment to stipendiary ministers), charity (donations or low profile lay ministry) and the capacity to coordinate other successful people. We should be very weary of this managerial variety of “shared ministry”. It is not the same as true cooperation based on spiritual principles. It is not loyal to the gospel in which the whole idea of success is turned upside down. And I think not being able to see the common ground of clergy and laity is a spiritual problem, too. So tackling that might be a good place to start our change of culture.

Conclusion

Well, in these two essays we have seen the development of Readership through the ages and a little bit about lay ministries in general. We have seen certain recurring patterns in that the Church needs her “army” of lay workers, but has not always managed to regard them as fully equal. In order to keep the laity motivated, though, the Church was always prepared to start new projects and experiments. The latest one is about a culture change. The necessary extent of the change is not always fully understood even by the initiators, but present and potential church members seem to require a shift in attitudes in order to become more active or join. The Church leadership made it seem as if this culture shift is already well underway. However, there are not that many signs that rules or attitudes relating to ministries have actually been relaxed, not even in the documents themselves.

I have documented several instances of contradictions, showing there is still a long way to go. The Church’s theological points of departure may not even be clear. It might help to realise that the very Gospel we all profess already holds the keys to a much needed change by focussing on much more radical types of equality and mutual service.

The future of Readership remains unclear, as its use has always been opportunistic. No other ministry has already seen so many changes. Mandy Stanton recommends her Readers “to be open to the possibility of doing things differently… to support and encourage those who suggest new ways of doing things and to help others to discover and develop their own gifts”. I agree, but would add that being Church is not only about an infinite variety of “doing things”, but also about theological consistency, identity and stability and about a truly shared and spiritual ministry. I doubt whether we now have a clear vision which we could call “Upbeat 2.0”.

The only thing which is clear to me is that it would be no luxury for our common ground as clergy, lay ministers, and indeed Christians in general to be rediscovered. Subsequently, we will want to cast aside all antiquated and artificial divisions, human doctrines, badly disguised prejudice, deliberate or habitual misrepresentations and unnecessary condescension. This would truly set God’s people free. I hope to experience a little more of this kind of liberty in my lifetime and to make my own small contributions as well.

Notes

[1] Sometimes purely symbolical privileges, like carrying the oils during Chrism Mass.

[2] Whither Reader Ministry, Gertrud Sollars, The Reader, Autumn 2014, Vol. 111, No 3, p. 33.

[3] cited Rhoda Hiscox Celebrating, p. 2, as cited in GS 1689, p. 35.

[4] In 1884, the Bishop of Bangor wanted ‘Christian men who can bridge the gap between the different classes of society; who, being in close communication with the clergyman on the one hand and the industrious masses on the other, can interpret each to each’ – cited Rhoda Hiscox Celebrating, p.14, as cited in GS 1689, p. 35.

[5] From Bishop Robert, The Reader, Summer 2015, Vol. 113, No 2, p. 34.

[6] No evidence was given. In Greek, two words, diakonia and leitourgia, are relevant. From the latter we got our word “liturgy”. Both Greek words can be translated either as service or ministry. They refer to different kinds of service, but that does not in itself make service different from ministry. It was only later that the meaning of “ministry” was restricted to “official service” (leitourgia) whereas diakonia could either be an office or an informal / personal service.

[7] It seems contradictory to both lower the average age and admit more people over 50. Also, it has never become clear to me in what ways it was made easier to be ordained after the age of 50. Perhaps the said recommendations were never actually adopted.

[8] From Bishop Robert, The Reader, Summer 2015, Vol. 113, No 2, p. 34.

[9] Looking to the future, by bishop Robert (then chair of the Central Readers Council), The Reader, Autumn 2016, Vol. 116, No 1, p. 5.

[10] From Bishop Robert, The Reader, Summer 2015, Vol. 113, No 2, p. 35.

[11] From Bishop Robert, The Reader, Summer 2015, Vol. 113, No 2, p. 35.

[12] See my first essay. Readers who fulfilled clergy vacancies during the wars, were called “drifting”.

[13] Olivia Rudgard, Religious Affairs Correspondent, One in six young people are Christian as visits to church buildings inspire them to convert, The Telegraph, 17 June 2017. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/06/17/one-six-young-people-christian-visits-church-buildings-inspire/

[14] Pen Wilcocks, The interface between the church and the arts, The Reader, Winter 2013, Vol. 110, No 4, p. 8.

[15] Although there is no evidence that St. Francis actually said this, at least two stories from his life illustrate his thinking. Francis once walked through a village with his brothers without saying a word. When the brothers enquired why they did not preach in the village, St. Francis told them, “We did preach”. The witness of their mere presence would have reminded them of previous sermons. Another time Francis warned his brothers for an eloquent preacher who failed to live out the faith he proclaimed. He said this preacher should endeavour to preach by example rather than by word. Although this does not show that Francis considered preaching unnecessary, it does show that proper behaviour takes precedence over saying the right words. In our times, when the Church has lost a lot of credibility, this applies even more. Also people no longer have the patience to listen to long verbal proclamations. Sometimes our presence can trigger questions, though.

[16] Mandy Stanton, Readers in a changing Church, The Reader, Winter 2015, Vol. 114,No. 4, p. 7.

[17] Although it can get difficult when “people act as ‘corks in the bottle’: doing everything themselves rather than recognising and encouraging gifts… delegating only the jobs they themselves do not want, micro managing all ministry… spending large amounts of time checking, changing and criticising anything which is not done exactly as they would have done it”. This is another quote from Mandy Stanton, where she is talking about difficulties at the chaplaincy level. Could it be that higher levels within the Church sometimes suffer from the same micro-management?

[18] Liz Shercliff, director of studies for Readers in the Diocese of Chester, in Hope and discipleship, The Reader, Autumn 2013, Vol. 110, No 3, p. 27.

[19] http://eurobishop.blogspot.nl/2017/06/lay-ministers-in-europe-moving-to.html?m=1

[20] Towards the Conversion of England, Church of England Commission on Evangelism, p. 61, par. 138, as quoted in “Setting God’s People Free”, GS 2056, p. 3

[21] https://www.christiantoday.com/article/will.thy.kingdom.come.fill.the.churches.wrong.question.says.the.archbishop.of.canterbury/109699.htm

[22] See the final section of my article on clergy and laity, https://www.emendatio.nl/clergy-laity-dualism/

History repeats itself. In 1866 the office of Reader was reintroduced after it was found that poorer areas and segments of the population had been neglected by the Church. On August 3, 2017, the website Christian Today reported Bishop Philip North’s words at the New Wine conference in Shepton Mallet as follows, “We are all trying massively hard to renew the Church. We are working like crazy, we are praying like mad, we are trying every new idea under the sun,’ he said. ‘Yet the longed-for renewal does not seem to come. In fact decline just seems to speed up. Why? Why are we struggling so much? I want to suggest that the answer is quite a straightforward one. It’s because we have forgotten the poor”. He also hit out at the failure of the Church to provide high-calibre leadership on estates, saying that “whilst many of those who do that work are heroic, we have to be honest and accept that some really struggle because their reason for being there is that it is the only job they could get. God doesn’t seem to be calling our best leaders to serve the poor. Or maybe he is calling, and we’re not listening.”

According to the bishop it is a matter of attitudes as well as distribution of funds. My conclusion is that if this is still a problem after all those years, it cannot be solved by delegating this to the laity, either. And it proves what I have been saying, that when Readers were doing a great job in poorer areas, the Church was not listening to them enough to make this kind of mission more structural and integrated and recognised.