If we want to discover the office of Reader in the New Testament, we are in for a hard time. There simply is no such thing, or it has not been recorded.[1] Over half of the epistles were written before the gospels and were read by whoever received them, probably the local overseer (chief elder). The fact that these letters may have circulated in a wide area before being collected in a version of the Bible[2] does not tell us anything about the way they were read, either. The gospels described a time before there were any Christian writings, so they did not mention reading from any Scriptures other than the Old Testament. It is generally agreed that, next to the Old Testament, the Early Church relied mostly on oral traditions. The oldest manuscripts containing the whole New Testament are from as late as the 4th century.[3]

Most references to reading Scripture are therefore connected to the Jewish synagogue, a kind of study and worship centre. A local caretaker “hazzan” was responsible for maintaining the building and organising the prayer services. Although the hazzan was in charge of the worship service as a whole, “the prayer leader, readers, and even the one who delivered the short sermon could be any adult member of the community. All were recognised as being able to share the meaning of God’s Word as God had taught them in their daily walk with him. In this way, the community encouraged even its youngest members to be active participants in its religious life”.[4] In other words, these were roles, but not offices. In a way, the situation resembles our time, in which any lay member in the church may read a scripture (except the gospel[5]). The office of Reader appears to be no more than a long interruption of this practice and, more recently, a formalisation of who, outside the clergy, was allowed to preach.

The first references to a Lector, namely with Church Fathers Justin, Hippolytus, and Cyprian, show us Readers who, building on this Jewish background, “would both read and expound the context of what had been read”, after which the bishop would preach. They were originally ordained with prayer and the giving of a Bible (according to Hippolytus) and/or by the laying on of hands (according to Cyprian).[6]

Around the year 200 (when Cyprian was born) “the Reader ranked very high in the Church compared with other ministers, and … in the Apostolic Church Order he took precedence over the deacons… Readership seems gradually to have declined, until by the end of the fifth century Readers were of little importance, and had become members of a minor order, and that minor order… was placed even below the minor orders of acolytes and exorcists.”[7] Therefore it is no surprise that no laying on of hands is found in the ordination form for the minor order of Readers in one of the Western Canons of the sixth century.[8] With John Wordsworth, Bishop of Salisbury, we can be amazed about the direction of this development, for it was essentially an “elevation of ritual and disciplinary officers [i.e. deacons; ed.] at the expense of an order of men who had the great duty of reading Holy Scripture to the people.”[9]

In any case, Readers (lectors) have been a specific order within the clergy and the hierarchy of the Church possibly since the time of Pope Soter, that is, for a maximum of around 1800 years.

In the (Eastern) Orthodox churches they still are an order within the clergy.[10] Candidates are first tonsured (a partial shaving of the head) to mark their admission to the clergy, then ordained in the same way as subdeacons, who belong to the major orders, namely by the laying on of hands.[11] Wearing a sticharion over a cassock, Readers will read from the Old Testament or the epistles, chant psalms and versicles, take care of the liturgical books and construct services. They may also be cantors, catechists and/or community leaders.

In the absence of an ordained reader, a layperson may read, but only after having received a temporary or permanent blessing from the priest. Readers are instructed to read Scriptures daily and, “as a member of the first step of the priesthood”, also to pray daily. The ordination service specifies that Readers must prepare themselves for a higher degree, but they are not immediately held to the standards of the higher clergy. Although they are definitely part of the clergy, Readers will generally not wear a clergy shirt (a shirt with a “dog collar” i.e. white band).

In the Western Church, the office of Reader slowly degenerated into just a formal stage in one’s career to become a priest. Church historian Dr. Francis Young, in his article “1866 and all that”[12], speaks of “lay participation in the liturgy” quickly waning in the West. Actually, this was not about lay participation, because in the Middle Ages the minor orders were still regarded as part of the clergy. Even as these orders were waning, these people were still being ordained.

By the later Middle Ages, this could take the form of ordination to the order of Acolyte, which was reckoned to encompass the other three. The task of Reader was carried out by any tonsured cleric, but not by the laity. In the earliest times of the English Church one of the most significant offices was that of the parish clerk. Originally they were ordained into a minor order and their role was to assist the priest. Gradually they took on functions such as reading the epistle. By the 14th Century not all clerks were ordained. It gradually turned into a lay ministry.[13] In the churches of the Reformation, only the sacred orders of deacon and elder/priest would remain.[14]

First revival

When “something resembling Reader ministry” emerged in the Church of England, it was, strangely enough, because of that same Reformation and “through expediency rather than design”. In other words, it had not been planned or based on theology but was thought to be convenient. Nicholas Orme, a Reader and church historian, gives us some details.[15] In the 1540s and 1550s, the Church of England had gone from Catholicism to Protestantism and back, then once more to Protestantism. Particularly in 1559, some Catholic clergymen resigned, not willing to serve in Queen Elisabeth’s re-established Church. Secondly, fewer men felt a vocation to the priesthood in these uncertain times. Thirdly, the dissolution of the monasteries by Henry VIII had robbed many parishes of their clergy. Fourthly, during epidemics clergy sometimes fled to safer areas. In other words, there was simply a shortage of priests, especially in poorer areas!

Archbishop Matthew Parker and other bishops then decided to license laymen to read services. The title “Reader” probably referred both to the ancient office (according to Nicholas Orme) and to the task of literally reading the service of the 1559 Book of Common Prayer (according to Francis Young). In any case, Parker argued that “Readers” were worth reviving. It was logical, therefore, that the first five Readers (January 1560, Bow Church, London) would be ordained, which they were.[16] Since that practice was not continued, it is usually considered an anomaly. Maybe we should turn this around and call it remarkable that the ordinations were not continued. The reason was probably a combination of Protestant ideas, rejecting the minor orders which, at the time, still existed in the Roman Church and the expectation that Readers would just be a temporary phenomenon.

The Reader’s duty was mainly to say morning and evening prayer and to take funerals. He had to promise not to preach, not to interpret Scripture and not to administer any of the sacraments. This simply meant that many parishes went without fresh sermons and without regular Eucharists. Readers were sometimes used as curates to work alongside clergy, but most, in a sense, took the place of clergy in poorer parishes.[17] There was a definite demand for Readers, who could minister throughout a Diocese. Otherwise, Parker would not have allowed them to be paid. Nowadays Readers are not allowed to accept payment. In those days some Readers needed another job on the side. This goes to show that others did not need a second job to earn a living. They could not rely on their income as a Reader, though, since they had to cease their activities “if any learned minister shall be placed there”.[18]

Another difference with today is that some Readers were probably ordinands marking time until they could be made priests. This echoes the situation in which the minor order of Readers was leading up to the priesthood. Today this would be frowned upon, as one is expected to have a vocation specifically for lay ministry. The position of one of the first Readers, Thomas Earl, was “regularised” in 1564 when he was ordained a deacon, which in those days allowed one to become an incumbent (holder of a benefice). These things not only illustrate that Readers were only ever a temporary measure, but also that there was not yet any objection against this being a transitory office, i.e. as a stepping stone towards the priesthood. Finally, candidates for readership were not expected to come forward on their own initiative. They had to be recommended by a local “patron” of the parish.

Adding up all these things, we can also conclude that these early ministers were not exactly pioneer ministers, in the way that the Church often wishes to portray them today. If pioneer ministry is what the Church needs today, or what she thinks she needs, it should not be projected back in time, claiming that it would be a return to something that was always intended. The first (Church of England) Readers clearly operated in a conventional parish-based system and were very much doing the kind of work priests either could not do or chose to delegate. This is also shown by the fact that they were not working alongside an incumbent. The fact that Readers usually operated in poorer areas, did not make this a pioneer ministry, either. They were simply doing as a paid job what the clergy would have been doing if there had been more of them.

The problem with using Readers in this way was of course that they could not fully replace deacons or priests. “In 1636 Bishop Barnaby Porter of Carlisle complained that he was compelled to ordain ‘mean scholars’ as deacons because the alternative was to leave churches and chapels served by Readers who could neither preach nor solemnise marriages”. Well, maybe they could preach, but they were not allowed to! Occasionally, in the dioceses of Chester and Carlisle, Readers were ordained as deacons “to regularise their ministry, even if they were tailors and shoemakers”.

I disagree with Francis Young’s statement that “Readers thus challenged the 18th Century church’s tendency to elitism and proved that leading worship was not incompatible with holding down a secular calling”. The elitism was never challenged, as Readers had unfavourable contracts and were continually, at the earliest opportunity, being replaced. They could not have been at the same time “tolerated as a necessity at the fringes of the Church” and a challenge to the elite. Again, there might be some projection going on here.

For instance, not all Readers were “holding down a secular calling”. As we have seen, a group of them made a living, being a Reader. If Readers had any significance as a challenge to the elite, they would not have all but disappeared by the early nineteenth century. Nicholas Orme adds in his article that “during the 17th Century the supply of clergy improved both in numbers and qualifications. The ‘High Church’ movement headed by Archbishop Laud preferred ministers to be clergy”. During the reign of King George II, in the 18th Century, “it was resolved that no one should officiate who was not in deacon’s orders” even though, by that time, High Church views had already been marginalised. “The existing Readers… were ordained without examination.”[19] There was little room for lay ministers. It was long before Vatican II and the Church could have re-introduced the minor orders, but they must have been happy with a simple, threefold ministry.

Second revival

Things started to change in 1839 with the “Victorian movement”, which is often considered as the “real” origin of Readers as we know them today.

Thomas Arnold, a married priest and headmaster of Rugby School, preached a sermon calling for the ordination of “distinctive deacons” as well as the creation of an order of “lay subdeacons” below them. Readers were often referred to as “subdeacons” in the literature of the period. Arnold’s concern was that an elite class of priests, almost all of whom had been educated at Oxford and Cambridge, were unable to effectively serve the lower middle and working classes. Hence the need for less educated deacons and a “supplemental agency” of subdeacons or Readers.

At the time, Church law did not allow ordained ministers to be in secular employment as well, so the distinctive diaconate did not take off. However, the second part of the proposal slowly gained acceptance. The main reason behind this was the competition from Methodism and other “nonconformist” denominations who did offer uneducated men the opportunity to become lay preachers. They were therefore already better positioned to attract the lower middle and working classes. The Church of England could not afford to stay behind. In fact, some dioceses had some lay ministers since the 1840’s, but this practice had not been regularised.

In 1864 two important events took place. The Young Men’s Society pleaded with the Archbishop of Canterbury to institute a “lower or special order” to “be added to the existing clergy… to carry on the work of the Church in its more secular and subordinate departments, and also peculiarly adapted to … sections of the community as yet but little reached by ordinary ministration”. The language used was a little circumspect. What was meant by “secular and subordinate departments of the Church”? Did the Church have a secular department? If so, why would it be subordinate? The term “laity” seems to have been avoided, but the intention was clear. The clergy was not addressing the needs of the whole community. The solution was sought in an additional “large body of earnest-hearted men”.

Also in 1864, the issue was discussed at “the Convocation”. The Catholic wing (High Church) would have preferred the new ministers to be ordained as deacons. Evangelicals advocated Readers “because” they, as Francis Young writes, “considered ordination unnecessary”. This can only be an understatement. Normally, if two parties try to reach an agreement and one wants something that the other does not mind, but only finds unnecessary, it would be granted. Surely, the evangelicals sternly opposed ordination.

Normally it is not expressed this clearly, but the conclusion can only be that in 1866 the evangelicals won. They were helped by the fact that there were already some un-ordained Readers and by the fact that it was hard, as I mentioned before, to change canon law. Even so, the issue came up again 20 years later at the Convocation of the Province of York (1884). These bishops wanted “a form of extended diaconate” instead of Readers. It took a joint meeting of the Convocations of York and Canterbury to arrive at a compromise. A system of Readers would be maintained, but they would be somewhat like deacons in that they were allowed to conduct worship and preach (in unconsecrated buildings).[20]

In 1904, again 20 years later, Bishop John Wordsworth’s report “Readers and Sub-deacons” appeared. There was still discussion whether Readers should be lay or ordained. The committee felt “it was not the time” to revive minor orders.[21] It sounded more like a pragmatic consideration rather than a matter of principle. To keep Readers satisfied they received another present. Now they could preach in church. As we will see, they were not to do this from the chancel. Also, it only applied to the better-educated (Diocesan) Readers. There were, you see, two kinds of Readers. “Parochial” or local Readers would only receive this privilege in 1921.

Four differences with the first revival are usually mentioned. Firstly, Readers were no longer a “stop-gap in the absence of enough ordained ministers”. Now they existed “for their own sake to serve a social need”. This, however, overlooks the similarities with the first revival. Readers were still deployed to reach an audience which the priesthood was apparently not able or not willing to reach. This time the latter was considered overqualified. I am sure, though, that part of the clergy was and is able to have meaningful communications with the lower classes. Also, I have my doubts about the supposedly sufficient numbers of clergy. There probably would not have been enough clergy if no Readers had been appointed. In that sense, they were still a stop-gap. Note also the wording in 1891 at the formation of a Diocesan Lay Readers’ Guild in Lincoln. It was formed “to give help to clergymen and others in the direction of mission work”.[22] This can hardly be explained as Readers existing “for their own sake to serve a social need”.

Secondly, there were now opportunities for less educated men to serve in ministry. This, however, is not a difference with, but a similarity to the first revival.

Thirdly, the focus on the lower middle class and the working class gave these classes a voice. It should be noted, however, that the upper classes tended to be represented and served by ordained ministers, while the lower classes tended to be represented and served by unordained ministers. Therefore, if the voice of the lower classes was heard at all, it was indirectly, through a lay minister who then had to explain matters to an ordained colleague. Add to this the fact that Readers were not (and still are not) represented in any synods as a separate entity. Any concerns of the lower classes would, therefore, have to reach the higher levels of the Church either via clergy who, by their own admission, did not understand them very well or via other lay representatives. In this situation, regarding Readers as an interface between “the church” and the lower classes (or even the whole laity) simply makes no sense. It could even be argued that by providing the lower classes with their own “kind of” ministers, class distinctions were more deeply ingrained.

Fourthly, as from 1884 Readers were licensed to preach. I think this was the only real difference. Services had to be led in an unconsecrated building. Then again, how much work was it for the clergy to consecrate a building once a Reader retired or was replaced? Until then, would the worshipping communities really have been that different from “normal parish churches”? Later on, in 1904 at the earliest, Readers were allowed to preach in consecrated buildings, but only from the chancel steps.[23] What an amazing (conscious or subconscious) reference to the ancient 7 steps leading up to the priesthood! The automatic and no doubt intended response of the congregation must have been, “He has not yet reached the chancel and the priesthood”.

Another similarity with the previous revival was that a significant number of Readers was still stipendiary.[24]

It remains for us to ask whether this second revival contained (or was even meant to contain) any pioneering. I am inclined to say no because the gospel had always been meant for all classes in society. This was simply, to some extent, rediscovered. It was not a grass-roots movement, as it was started by a prominent clergyman and, before that, in other denominations. The decision to use “less educated men” was not new either. The license to preach, although new, assumed that the lower classes were used to attending church already (before urbanisation drove them into the cities) and therefore could be reached via preaching in Sunday Schools and Mission halls. It should also be noted that when (from 1891 to 1901) “the small but growing band” of Diocesan Readers in Lincoln led services, they did so “by invitation” from a number of Christian institutions.[25]

This was not pioneering in the sense in which we use the term today, namely of reaching out to those not currently attending church, using all kinds of venues, not linked to a church, modern communication technologies, etc. Nevertheless, it took the Church 22 years (from 1844 to 1866) to make a start. Thomas Arnold would not see it happen. He had died in 1842 at the age of 46.

Third revival

Reader badge from Manchester. “Tolle lege” means “take and read”, a reference to the conversion of St. Augustine.

During and following WWI and WWII, which followed one another quickly, large numbers of clergy became chaplains to the forces and many lost their lives. Readers filled their places, at least as far as the non-sacramental ministry was concerned. There were not even enough male candidates and that is how women came to be admitted as well. These women were called “messengers of the bishop”, but of course they were simply Readers. They would have to wait for that title, though. It came in 1969.

“Readers were becoming increasingly numerous but were not universally appreciated.”[26] In 1921 a Reader wrote “Lay Readers in theory are a necessity, in practice they are not wanted by the bishop, clergy or congregation… In most parishes the wealthy layman has priority over any licensed Reader”. That same year, however, a vicar in Leicester was full of praise about the work of Readers while he had been ill for 6 months.[27] Could it be that both perspectives were correct? People were pleased with the work that Readers did, but would still prefer to have a priest? Readers had some authority, but without ordination they were no match for wealthy fellow-laymen?

The answer was to make Readers look a bit more like priests. The regulations of 1921 emphasized that admission was for life and in that respect comparable to ordination. Only a couple of generations ago the typical blue tippet or scarf was added to the typical Reader outfit. The scarf itself was a compromise. It was not to be called a stole and no liturgical colours or variations were permitted. The name “tippet” is usually also avoided as it could be worn by a priest, although it would then be black (preaching scarf worn with choir dress when there is no Eucharist). At least in those days the Church still recognised the important role Readers had played during the wars.

Nowadays the Church speaks of “drifting” Readers. We may as well ask why the clergy was not described as “drifting” into the armed forces. Surely there was no voice from heaven telling them to do so and get themselves killed. Many will say, though, that it was a heroic thing to do. That may be so, but in that case, we have to ask if it is really appropriate to give all the glory to the martyred army chaplains while ridiculing Readers for helping out by (in the same context) calling them “general ecclesiastical factotum”.[28]

I had to look up this word in the dictionary, as my native language is not Latin, unlike those who consider their roots to be in the Church. Factotum means someone who does everything (which is either asked or needed), an odd-job man, handyman, a jack of all trades. I fully admit that Readers often accept too many responsibilities. A colleague who heard that I did not have any preaching appointments for a while, said, “A Reader will always find something to do”. He sounded as if that was a valid definition of readership or a proper use of our training. Needless to say, I disagreed with such a view. I find it striking, though, that the Church seldom complains when we do lots of things which do not require any qualification (which may keep us from doing what we are good at) but is completely alarmed when we do something even remotely “clerical”.

Let me illustrate this with a small anecdote. An alb can be worn with a rope around the waist, a so-called cincture. This rope can then also prevent a stole or scarf from flapping around. At one time I was doing something like that with my blue Reader’s scarf. All these things I am allowed to wear. However, my chaplain at the time, a person I still deeply love and respect, told me not to fasten my scarf like that. The reason he gave was that the scarf was a token of my office as a Reader, so I should not cover it, not even locally, with a cincture. Now, this could not possibly be the real reason because clergy often completely cover their stole with a chasuble. Did they not respect the token of their office?

The real reason had to be that I looked perhaps a tiny fraction more like a clergy person than the average Reader. This, apparently, was felt as a threat. I don’t think the chaplain himself felt threatened, so it must have been a warning that other clergy would be offended. Later, another chaplain warned me that in the Church of England everything is considered to be a signal of some kind. There are, for instance, three kinds of cassocks which can hardly be distinguished from each other. A double breasted cassock means you are an evangelical! I had never realised it. How terrible it must be to live in constant fear that you are giving the wrong signal. Or that you should have to depend on such signals. Had we really entered the 21st century? Did flexibility really have to be called “drift”?

We must, however, return briefly to 1930. There was another major debate on Readers and the diaconate. The Lambeth Conference published a paper which speculated on the ordination of men in secular employment.[29] It would remain speculation, but by way of compensation, in 1941, Readers were allowed to administer the chalice and read the epistle. These privileges, by the way, would cease to be Reader’s privileges when in 1969 other lay people were allowed to read even the Gospel and administer the bread at Holy Communion.[30]

Canon John Murray, Secretary of the CRB until 1944, had wanted to go further. “If we are to do that [authorize Readers to administer the chalice; ed.], surely the simplest and most effective plan is to ordain them outright as deacons”. He added that for half a Century Readers had responded to a call “to do the work which, in our ordinal, is the distinctive work of the Diaconate… And yet the rank and file of Churchmen are barely conscious of their existence”. A motion was approved in the CRB to ask bishops to “ordain as Deacons men who have given proof of their spiritual and intellectual capacity by faithful service in the Office of Reader”.[31] And then it became silent, at least on this subject!

A small “Peasants Revolt”

Most Readers are no longer allowed to be paid for their services. I am not sure exactly when this started. Certain other lay ministers are stipendiary. What you can get for free is not always appreciated as much as that which comes with a price tag. Sometimes I wonder if privileges like being allowed to preach are not used as a payment in kind. Francis Young did mention the “opportunities for less educated men” in the context of “social needs” and allowing voices to speak. If, however, Readers were only talking to themselves or to the lower classes they were supposed to represent, they were receiving as the Dutch would say, “a cigar from their own box”. The feeling of being tolerated “because we have to have lay ministries” may further have been fed by the use of the term “admission” instead of “ordination”. It made it sound as if Readers had received a complimentary ticket giving access to a club or to one of the lower levels of a secret society.

Leading up to the CRC meeting of 2006 the morale among many Readers had become low for other reasons as well. They “had fallen into a kind of no man’s land between on the one hand a much larger number of voluntary ordained ministers [OLM] and on the other hand a rapidly growing number of unlicensed lay ministers, generated by a variety of diocesan lay training schemes. Add to this the growth in services of the Eucharist and the decline of non-Eucharistic services, at which Readers can officiate, and it is understandable that Reader morale was affected.” [32]

It was not as if the Church had not been warned. In 1970, Bishop Robert Martineau, himself originally a Reader, said Readers “have just the qualities which a selection panel would look for in an auxiliary priest.”[33] In 1973 Canon King (CRB) had written that with a “changing habit of worship [there is an] increasing need in the Church for ministers who are authorised to celebrate the Holy Communion.”[34] In 1983, Canon Tiller (ACCM) wrote, “where there is a suitable Reader… there is a strong case for calling such a person to a local sacramental ministry as well.”[35]

During a Synod debate in 2000 about the new service of “Communion by Extension” some had argued that the ordination of more people would be theologically more acceptable.[36] This whole liturgy could be seen as another forced attempt to expand the authorisation of Readers without having to ordain them. Nothing changed after these sensible remarks, accept perhaps that ordained local ministry slowly went out of fashion again (except in Canada), but the need for ministers who could baptise and celebrate Holy Communion staid. This was just not filled in with Readers. And if they wanted to be ordained, they almost had to start from scratch. Between 1982 and 2004 the number of Readers in training dropped from 1714 to 1081. By the way, I was one of the 1081. Bad timing, perhaps.

It was not only the Readers themselves who complained. For instance, Revd Colin Randall found that Readers can be very gifted at taking family services, but in rural churches they cannot proceed to baptise the children in those families, which often means that a retired clergy person has to be flown in. This does not make sense to the families. In emergencies (such as the child dying), any lay person could already baptise. As early as 1963, the then Central Readers’ Board (CRB) asked for permission for Readers to be able to baptise. In 1990 and 1991 the then chairman of the CRC, Bishop Michael Baughen, said permission should soon be granted. He added, “What saddens me… is to see how desperately slowly changes have taken place… The deep opposition to lay ministry… still lingers on.”[37] Many years had passed since.

So now the Archbishops’ Council was asked “to consider how the office of Reader should be developed and Readers more fully and effectively deployed”, given that the recently introduced new ministries and other circumstances should remain. Interviews were held and a report was produced, called “Reader Upbeat – Quickening the tempo of Reader ministry in the Church today”. [38] It spoke of “the current crisis in Reader ministry” (page 22) and contained some 30 recommendations and action points.

Before presenting these at the General Synod of 2009 the Bishop of Carlisle, Rt Revd Graham Dow, explained why the working party had not recommended “extensive” transfer of Readers to ordained ministry. First, “many Readers greatly value their lay status”. This, however, implied there were also Readers who would not mind being ordained. In fact, the report showed that most would consider that to be a logical step. It would solve many problems with leading services, baptising, marrying, etc.

Interestingly, the Bishop of Europe, Rt Revd Geoffrey Rowell, said that the distinctive diaconate would be first in line to assist with baptisms and it deserved strengthening. However, that strengthening, too, was and still is long overdue. If the diaconate had been strengthened in time, there might never have been a Reader ministry. Was the Church now robbing Peter to pay Paul? Moreover, I would think that the transfer of a number of Readers to the distinctive diaconate would actually constitute a strengthening. So I am not sure what the Church was waiting for. I suspect that those Readers who preferred to stay in a lay ministry, often said so because the distinctive diaconate was / is not ready yet.

So it could also be an option to accelerate the strengthening and transformation of the diaconate, rather than just presenting us with a closed door. Unfortunately, there was no more mention of the fact that the report, on page 23, cites the important work of the Roman Catholic theologian J.N. Collins in 1980. Most theologians either believe that baptism qualifies a person for the work of ministry, or they agree with Collins that not all service should be called ministry and that it is the domain of deacons. The problem is that while the Anglican hierarchy seems to reject an “all-member-ministry” they cannot bring themselves to accept Collins’ logical conclusion “that lay ministers like Readers should be ordained deacon”.

The second and allegedly main reason for not ordaining Readers was that they were needed as “a clear sign of partnership between clergy and laity”. They were an “important model of lay participation” and a “stimulus to others to interpret life theologically”. It is very questionable though, whether most church members even realise were the exact demarcation line between clergy and laity is currently located. Many mistake Readers for clergy, anyway. That is the reality. Therefore this “sign of partnership”, if it exists at all, will not be a very “clear” sign. It is also not clear why all the hard work done by unlicensed laity could not just as well serve as a model. Just think of all the people faithfully doing the collections, the intercessions or the welcoming.

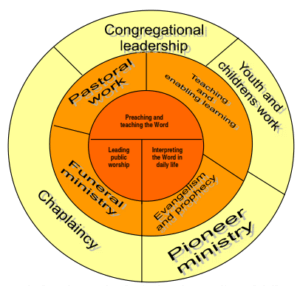

It is, however, trendy to explain various roles in the Church as “signs”. I value such “iconic” aspects when speaking about the inner dimensions of religion and spirituality, but how useful is this approach for defining a dozen different roles in an organisation? A deacon is described on page 39 as “a sign of the calling of all Christians to service”. A priest is described as “a sign that all Christians share together in Christ’s royal priesthood”. “The bishop is a sign that God provides oversight”. Then the report even contradicts itself, saying, “Lay ministries … do not have symbolic significance in the same way as a sign of God’s gift and calling” (underlining my own). Well, if a lay ministry is not a sign of a particular gift or calling, how can it be a clear sign? And if it is a sign, but not in the same way as priests or deacons have symbolic significance, how is this sign different? These questions were not answered.

This way of describing or understanding ministries can never be a solid foundation for a particular classification of ministries and roles. For instance, we would be equally justified in creating a new ministry, called “Hearers”, who are then defended as a sign of the need for all Christians to listen carefully to the Word of God and the needs of the world. We would proceed with 30 recommendations to encourage this ministry of “Hearers”, to develop training programs and to ensure collaboration. We would even find many incontestable clues in the New Testament that listening is important. Yet this would neither be a satisfactory doctrine of the Church, nor a good approach towards the innovation of an organisation.

Most importantly, if the distinction between clergy and laity would be less hammered home[39], there would hardly be a need to have a specific sign (in the form of Readers) that cooperation between the two camps is possible. That cooperation would then be more natural. Finally, it is questionable whether it would actually have a demoralising effect on other laity if many Readers were to be ordained to the diaconate (page 41). Yes, their public ministry would be “clericalised”, but that does not have to be the same as “clericalism”. Yes, their public ministry would lose “its significance as a public lay ministry”, but they could still (maybe even more so because of their background) “demonstrate that the church is for all, not just clergy”.

I believe that the best way to encourage participation is for policy making clergy to exit their ivory towers, rather than relying on a buffer of lay ministers for their PR and for the “incarnational” presence of the Church. This can be done by openly admitting and explaining that the whole distinction between a professional clergy and a vast sea of cooperating (or not) “lay” people is little more than a pragmatic human construct and a pseudo-theological fabrication.[40] It might also help to honestly admit and communicate that the spirituality of the clergy is not fundamentally different from that of the laity.[41] Then the “laity” would be truly encouraged, set free and also feel more responsible for mission.

Recommendations

Given that the task group was not going to allow any upward “border-crossing”[42] and no pruning or standardisation of lay ministries (which was not their brief, anyway), what did they recommend? The most important recommendations were:

- “to have clear working agreements, regular ministerial reviews [then only for 50% of all Readers], support for continued ministerial education, pastoral care, regular attention to their ongoing personal development and vocation, and that they receive the regular letters that bishops send to their licensed clergy”. Some of these recommendations, like the one about working agreements, were not new. Sadly, the acceptance of this report did not mean acceptance of all recommendations, either. Every Diocese (bishop) could decide not to implement some of these measures, as long as they reported some measures back to the task group by 2010. Personally, I have had the benefit of continued ministerial education (CME) but have never been offered any ministerial or vocational reviews between 2005 and 2017. I have never been asked if there was a clear working agreement. There was none.

- The next big thing was the introduction of the new title of “Licensed Lay Ministers”. This was first intended to cover Church Army Officers as well, who are also lay ministers and hold a license. However, the Church Army Officers themselves thought this was a really bad idea. Nobody had consulted with them about it, either. This means that the term LLM would be almost synonymous to Reader. With many regarding “Reader” as antiquated and as not describing what the person actually does, LLM has become popular. It could still cause confusion, though, because “under Canon E7 some bishops have issued people with licenses as lay workers, usually as youth workers or pastoral workers.”

- Opening up possibilities on the boundaries of the Church.

It was claimed that the report clearly showed that when Reader ministry was reintroduced in the 19th Century, it was to meet the needs on the boundary of the existing congregations. This vision was to be regained by engaging in Fresh Expressions and various forms of chaplaincy. This was called “incarnational” ministry, to “go where people are”. This raises the question, although apparently nobody dared to ask it, whether lay ministers can actually be more “incarnational” than clergy, who represent Christ. As we have seen, it is also questionable whether today’s challenges can be compared to the ones of the 19th Century. Most importantly, like with all good inventions, pioneering does not produce results because we want them, but because of certain favourable conditions, time and answers to prayer. The recommendations from 2009 relied too heavily on manufacturability and wishful thinking, while making minimal actual changes nationwide.

- Making far greater use of Readers both in the local church and wider into the deanery. The first part, about the local church, is puzzling. The whole problem was that due to several factors, Readers were used less in the local church, and fewer people were attracted to Reader training. The second part sounds like a good idea, all depending on whether it would be adopted and on whether neighbouring churches would in fact be able to deploy Readers in better ways. However, the report admits on page 37 that “there are few requests for leading and preaching outside the Reader’s own parish, since NSMs and retired clergy are chosen in preference so that they can celebrate the Eucharist”!

The task group did a good job when it came to listing the various problems, obstacles and challenges in Reader ministry. My main criticism is that it tries to fight pragmatism with more pragmatism. It is hoped that somehow the multitude of recommendations will have some effect, but none of them were binding.[43] This means that the lack of uniformity across the Dioceses could hardly be expected to diminish. Some people grabbed the opportunity of this confusion to even promote a conversion of Readers into Church Army evangelists. If flexibility is the only requirement for Readers, than why have any job description?

I tend to agree with Mr. Robin Stevens, a Reader from Chelmsford, who said, “Two and a half years ago we agreed that the under-use of Readers needed to be addressed… Only this week I spoke to a lady who had been a Reader but on a change of incumbent the new incumbent did not want to use her. She feels hurt and abused, not under-used. When I attend Readers’ meetings I hear a litany of complaints about the relationships between Readers and clergy leading to under-use, and I do not think that this report has addressed that major issue”.[44]

Exactly, what the report basically said was, “we can see that by changing worship patterns and lack of awareness we have caused some collateral damage here, but reversing that is out of the question, so why don’t we all look for other things for you to do?” On the other hand, if Readers had paid more attention to their own history, they would have known that there has always been a lack of agreement about their identity and core ministries, leading them to be valued at one time and discarded the next. The comparison with eating crumbs under the table imposes itself (which does not have to be shameful). Nowadays, though, there are many more dogs, fewer tables, and Readers are more emancipated and not so easily dismissed. It is not so much that Readers are needed as a sign of collaboration, but that the Church cannot afford for them to become a sign of the laity not being taken seriously, in spite of Readers having been backed by a succession of bishops.

In chapter 3, “the current picture”, the report makes a sudden transition from the description of the history of Reader ministry and the current picture, to a Mission Based theory in which the bishop determines everything that goes on in a particular Diocese. “The bishop can delegate and share functions of teaching, pastoral care and sacramental provision. He will do this both by working with the priests and deacons… and by allocating such responsibility to lay persons as best fulfils the Church’s mission and is within the boundaries of the Canons and regulations of the Church of England”.

So what are we even talking about? If there are any problems with lay ministry, the bishop will solve them within the current Canons and regulations! I have written a separate article / chapter about the ownership of mission. You can find it here: https://www.emendatio.nl/chief-missionary-fallacy/ In the meantime the report disqualifies itself by giving such a simple solution. This is also the chapter that goes on about every ministry being a “sign”. It has little to do with “the current picture” and everything with, to phrase it generously, an attempt to keep all options open. A wasted opportunity, as far as I am concerned, not a “quickening of tempo” as the subtitle of the report had claimed.

My worst suspicions about the fate of the report were confirmed in 2017 when I tried to find out what the response of my Diocese had been in 2010. Although the responsible bishop remembered having responded, this response could no longer be located. In spite of my disappointment I was still expecting to find some discussion of the reactions from the various Dioceses in the minutes of the July 2010 sessions of General Synod. Even that proved not to be the case!

There were just two questions about the differences in procedures for transferring Readers between Dioceses and one about the reactions to the report. The Chair of the CRC (Central Readers Council) answered[45] that the CRC was preparing guidelines for the transfer of Readers. He admitted that the Reader Upbeat report had “not been read widely”, but denied that it had offered little hope for the future. The strong leadership for, as one Reader had put it, “sorting out the ministerial confusion” would be provided by “the Reader executive” including himself. His present scope, however, was different from the one of the report. He was no longer concerned with Readers, but with “any form of lay ministry, including Readers, and gaining recognition … of licensed lay ministry”.

From this, my Diocese concluded in 2017 that “the thinking about the future of Reader ministry had moved on since the issue of Upbeat …So it seems as though this document simply ceased to have any relevance at this point.” What had really happened, though, was that the decisions were now being made in smaller forums and with less transparency. Also, certain valuable recommendations would not return in later statements on Reader ministry. The Church seemed to have run out of acceptable compromises.

Notes

[1] The GS 1689 report states on page 22, “the Greek words episcopos, presbuteros and diakonos which are translated into English as bishop, priest (or presbyter) and deacon respectively can be found at least occasionally in the pages of the New Testament. In contrast, there are no apparent roots for Reader ministry within the writings of the New Testament.”

[2] Cf. Colossians 4:16, Revelation 1:3.

[3] http://www.helsinki.fi/teol/pro/_merenlah/oppimateriaalit/text/english/newtest.htm

[4] https://www.thattheworldmayknow.com/he-went-to-synagogue

[5] The bar to “lay” people reading the gospel is Roman Catholic and was copied by Anglo-Catholics in the Church of England in the 19th Century. The Oxford Movement is responsible for that.

[6] GS 1689, page 28, 2.6.1.

[7] T.G. King, Readers: A Pioneer Ministry, London, Central Readers Board, 1973, pp. 54-55, as quoted in GS 1689.

[8] Michael Nazir-Ali in Shapes of the Church to Come, Eastbourne, Kingsway, 2001, p.164-5. He refers to Joseph Lienhard SJ, Ministry, Message of the Fathers of the Church Wilmington, Michael Glazier, 1984, pp. 37,42,132

[9] John Wordsworth, The Ministry of Grace, London, Longmans, 1901, cited by King, Readers, p. 60, cited in GS 1689.

[10] https://orthodoxwiki.org/Reader

[11] In the Orthodox church, the ordination of deacons, priests and bishops takes place by cheirotonia, “to stretch out the hands”, instead of Cheirothesia – literally, “to place hands”.

[12] The Reader, Summer 2016, Vol. 115, No 2.

[13] GS 1689, page 29, 2.6.3.

[14] These would later be called “offices” and the chief elder would be called “minister” or “pastor”.

[15] The Reader, Autumn 2016, Vol. 116, No 1.

[16] By Bishop Meyrick of Bangor. Reference to the actions of Archbishop Parker and Bishop Meyrick can be found in T.G. King Readers: A Pioneer Ministry, London, Central Readers Board, 1973, pp. 67-68.

[17] Readers in the reign of Queen Elizabeth I ministered in poorer parishes ‘destitute of incumbents’. G. Lawton Reader-Preacher London, Churchman, 1989, ch.9 cited by Rhoda Hiscox Celebrating Reader Ministry, London, Mowbray, p.12.

[18] One of the declarations in Matthew Parker’s instructions, dating from 1560.

[19] Richard S. Ferguson Diocesan Histories – Carlisle, SPCK, 1889 p.174, as cited in GS 1689, p. 30.

[20] T.G. King, Readers, pp.90, 91, 110, as cited in GS 1689, p. 31.

[21] Readers and Sub-deacons (Convocation of Canterbury no.383), as cited in GS 1689, p. 32.

[22] The Minute Books of Lincoln Diocesan Lay Readers’ Guild, Diocese of Lincoln Archives, as cited in GS 1689, p. 31.

[23] Margaret Tinsley, Reader and Lay Canon, in Regional Readers rejoice!, The Reader, Spring 2017, Vol. 117, No 1, p. 32.

[24] GS 1689, p. 33.

[25] The Minute Books of Lincoln Diocesan Lay Readers’ Guild, Diocese of Lincoln Archives, as cited in GS 1689, p. 31.

[26] GS 1689, p. 33.

[27] Rhoda Hiscox, Celebrating, p.22, citing The Lay Reader, xviii, January and June 1921, as cited in GS 1689, p. 33

[28] Looking to the future, by bishop Robert (then chair of the Central Readers Council), The Reader, Autumn 2016, Vol. 116, No 1, p. 5.

[29] The Staffing of Parishes (Church Assembly), as cited in GS 1689, p. 34.

[30] GS 1689, p. 34, 35.

[31] The Lay Reader 1931, as cited in GS 1689, p. 34.

[32] GS 2009 tsat3j08, Discussion of GS 1689, p. 281.

[33] Robert Martineau The Office and Work of a Reader , London, Mowbray, 1970 pp.5,6, as cited in GS 1689, p. 36.

[34] T.G. King Readers, p. 163, as cited in GS 1689, p. 36.

[35] John Tiller A Strategy for the Church’s Ministry, London, CIO, 1983 p.130, as cited in GS 1689, p. 36.

[36] General Synod Report of Proceedings 31.2(July 2000) p.252, as cited in GS 1689, p. 37.

[37] In the foreword to Rhoda Hiscox Celebrating, p.vii, as cited in GS 1689, p. 35.

[38] “Reader https://www.churchofengland.org/media/1251959/gs1689.pdf

[39] Here is just one of many illustrations. Although most of those ordained will agree that baptism and Holy Communion are not surpassed by any other sacrament (see: https://www.emendatio.nl/spirituality-one-two-types/ ), most will draw considerable attention to the anniversary of their ordination while not drawing attention to the anniversary of their baptism. Their words and their actions are simply saying two different things! Most clergy clearly regard ordination as more special than baptism or confirmation.

[40] See https://www.emendatio.nl/clergy-laity-dualism/

[41] See https://www.emendatio.nl/spirituality-one-two-types/

[42] The Archdeacon of Newark called the issues concerning baptism, Communion by extension and the relationship to other ministries “sorts of border dispute” and “confusions” such as would result from the lack of “a core understanding of the character and order of the Church of England”. He therefore urged the formation and training of Readers to place more emphasis on such a core understanding of existing rules, especially since candidates for all ministries often have no Anglican background. In so doing, he overlooked that the existing rules do not always answer the existing needs and that clergy were asking for changes as well. Plus the fact that the borders changed when the number of Eucharists increased.

[43] Reader ministry is regulated by Canons E4, E5 and E6 and the Bishop’s Regulations for Reader Ministry 2000. The report does not request for these regulations to be revised, but states that if the recommendations are accepted, this would be an opportune time to revise the regulations. It has never become clear whether the recommendations had been accepted or not. When it comes to variations between the Dioceses, the report goes no further than to note that concern has been expressed.

[44] GS 2009 tsat3j08, Discussion of GS 1689, p. 294.

[45] https://www.churchofengland.org/media/1155179/july%202010%20consolidated%20with%20index%20(with%20full%20bookmarks).pdf (removed in 2019), page 64.

[…] ← Previous […]